It would be no exaggeration to say that Berlin is one of my favorite cities in Europe. It’s one of those wonderful places where there is so much to see and do that it’s hard to imagine ever getting tired of exploring all that the city offers. After three visits to Berlin, the most recent of which was a research trip this summer, I still feel as though I’ve only scratched the surface of all there is to discover in Berlin – and all there is to discover about Berlin. Whenever I’m in Berlin, one of my favorite things to do is to simply wander through the city, exploring the neighborhoods that I pass through and enjoying the sense that history is all around me. When I say the sense that history is all around me, I don’t simply mean the fact that I’m surrounded by historic buildings – the physical reminders that Berlin is several centuries older than the United States. Instead, it’s something more intangible, a feeling that the past is never truly past (to slightly misquote William Faulkner), but rather something that lingers not very far below the surface of present-day Berlin.

Of course, given Germany’s decades-long efforts to come to terms with – and publicly memorialize the victims of – its Nazi past, there are reminders of Berlin’s complicated history everywhere throughout the city. To name just two examples, the thought-provoking Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is directly adjacent to the famous Brandenburg Gate. In front of the Bundestag, Germany’s federal parliament building, is a memorial to the legislators who opposed Hitler as he consolidated power in the first years of Nazi rule. I recommend that any visitors to Berlin visit these memorial sites, especially given their location at the heart of today’s tourist Berlin. However, given a bit more time in the city, I would encourage any visitor to Berlin to dig a bit deeper, so to speak, and take a detour from the well-worn tourist path to seek out a few of the many less well-known sites in Berlin at which the past is tangible beneath the surface of today’s Berlin.

Anyone planning a trip to Berlin has likely discovered that one of the recommended stops for tourists is Checkpoint Charlie, a former border crossing between West and East Berlin. Because Checkpoint Charlie was a crossing point designated explicitly for non-German travelers and Allied military personnel, American tourists often tend to consider Checkpoint Charlie as one of the symbols of divided Berlin. And for Americans traveling or living in West Germany who decided to take a short trip to the other side of the Iron Curtain, and who crossed the border into East Berlin at Checkpoint Charlie, this particular border crossing was certainly the symbol of their personal experience of Germany’s division during the Cold War.

However, for Germans, there is a different symbol of their personal experience of divided Germany: the Friedrichstrasse train station in central Berlin and the nearby Tränenpalast, or “Palace of Tears.” The Friedrichstrasse station was a border crossing used by Germans (West Germans) returning to West Berlin from East Berlin, usually after having been permitted to visit relatives in East Germany. The Tränenpalast, a building adjacent to the train station, earned its name from the tears shed in front of its departure hall by parting relatives, who were forced to say their goodbyes before the West German family members entered the building to go through the necessary customs and border checks to return to West Berlin, not knowing when (or if) they would be able to see their relatives again.

For the East German members of these families, the parting was doubly hard, as they could not be certain when they would see their loved ones again, but were quite certain of the knowledge that they themselves were largely unable to cross the border. Now a memorial site, the Tränenpalast is one of the many places in Berlin where the past is tangible beneath the veneer of the present. A visit to the memorial exhibition is a sobering reminder that, while today Berliners and tourists alike pass easily through the Friedrichstrasse station, not so very long ago, it was the site where East and West Germans alike faced the solid, unyielding reality of the border and of the division of their country, their city, and their families.

If contemplating the recent history of the Friedrichstrasse station is a weighty reminder of the families torn apart by Germany’s Cold War division, visiting one of the former “ghost stations” is a way to learn about one of the greatest absurdities of the division of Berlin: that, even as the city was divided, first by sector borders and later by a wall, it remained connected by its transportation system. From 1961 to 1989, three U-Bahn and S-Bahn lines actually passed through East Berlin stations on their way between West Berlin stations. These East Berlin stations became known by West Berliners as “ghost stations,” as the trains passed through the stations without stopping and the only people on the dimly-lit platforms were East German border guards. For residents of and visitors to West Berlin alike, the presence of the “ghost stations” made for a rather uncanny transportation experience: knowing that you are passing through foreign territory on an otherwise ordinary commute or trip through the city. For East Berliners, who were not allowed to use the train lines that passed through the “ghost stations,” these stations disappeared from their mental maps of the city, as the entrances were boarded up or, at times, erased entirely from the urban landscape. Since the Berlin Wall fell, the “ghost stations” are once again alive, though their peculiar history lingers in the air, particularly at the Nordbahnhof S-Bahn station, which now features an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition about the “ghost stations” and the day-to-day realities of life in a divided city from the perspective of West Berliners, East Berliners, and the leadership of the GDR (German Democratic Republic, or East Germany).

Continuing with the theme of transportation-related sites, another place in Berlin where the scars of the past are readily visible today is at the Grunewald S-Bahn station in far western Berlin. Many visitors to Berlin pass through Grunewald on their way to Potsdam, or get off the train at Grunewald to enjoy the large nearby forest, without pausing to explore the history of the train station itself. However, if you take the time to explore the Grunewald train station itself, you will notice that there are signs to Gleis (Platform) 1-4 and to Gleis 17. Why the discontinuity? It is because Gleis 17 is no longer a working platform, but a memorial to the tens of thousands of Berlin’s Jews who, during the Holocaust, were deported to ghettos and death camps from the same station through which commuters and tourists now pass everyday on the S-Bahn. When you first climb up the stairs to Gleis 17, it looks much like a train platform, one that has become overgrown with time.

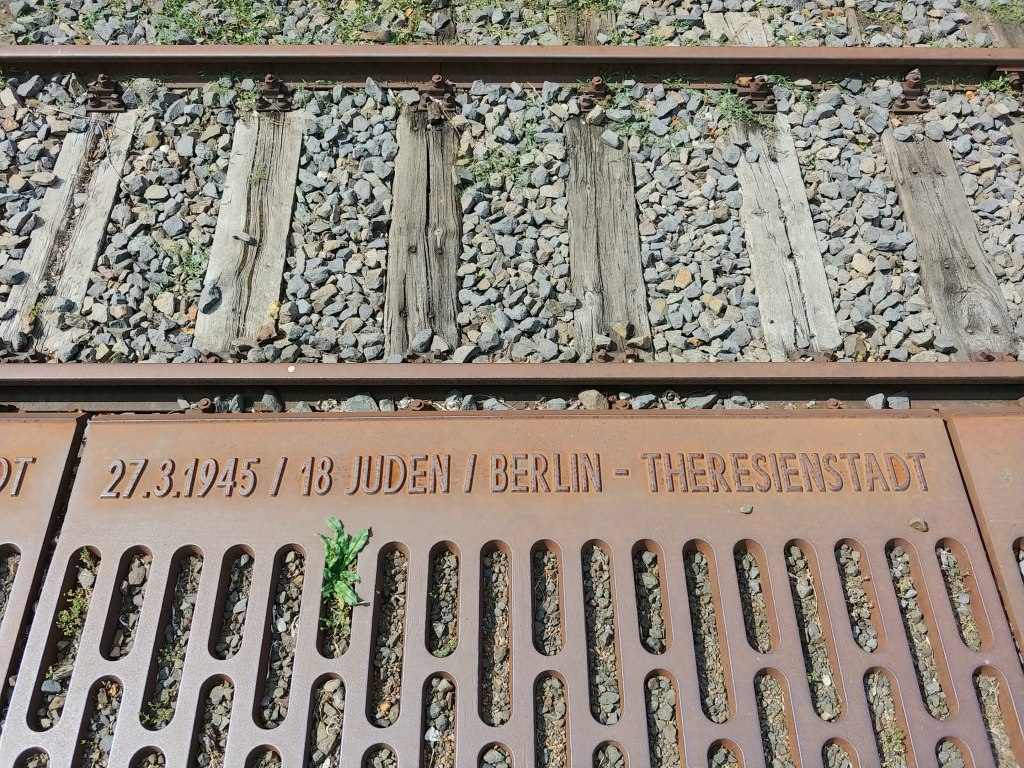

Upon closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that this is, of course, no ordinary station. The platforms where so many people stood before being herded onto trains that often took them to their deaths have been replaced with memorial platforms, so to speak, upon which each deportation from Grunewald is noted, with the date, destination, and number of Jews deported inscribed.

Walking the length of the two memorial platforms reveals the enormity and fervency of the Nazis’ attempts to murder Europe’s Jews. Regarding the enormity of the Holocaust, it takes the full length of the two platforms just to list all of the deportations from this one station (contemplate that for one moment). Regarding the fervency with which the Nazis embarked upon the Holocaust, the date of the final deportation listed is March 27, 1945, just over one month before Berlin fell to the Soviets and Germany surrendered to the Allies (now contemplate that for a moment).

I can only say that, having visited the Gleis 17 memorial at Grunewald on my most recent trip to Berlin, the next time I pass through Grunewald station, the fate of those deported from there during the Holocausat will not be far from my mind.

Is the past ever truly buried? For some cities, the answer would be perhaps. For Berlin, the answer is a decided no. Between Germany’s attempts to come to terms with and publicly acknowledge its Nazi past and the scars that decades of division left upon the fabric of the city, Berlin is a city where the past is ever-present, lingering as you wander through its neighborhoods and soak up its vibrant spirit. So, the next time you are in Berlin – whether for the first time or the tenth time – get off the traditional tourist path, visit one of these sites, and come to your own conclusions about the presence of the path in Berlin.

Leave a comment