Being about a month away from graduating with a master’s degree in history, a question I often get is: what is your thesis about? This is a question that is deceptively hard to answer. After spending several months researching my thesis – reading books, gathering newspaper and magazine articles, watching films – and several more months writing and revising it, I know all the ins and outs and little details of my topic. I could probably talk for an hour or more about my thesis, discussing one interesting fact after another and going into all the minutiae of my argument and its historiographical relevance. But, because this is not an academic journal and readers of this blog are not looking for the same things as my thesis committee, I will attempt to make my thesis accessible to a broader audience.

The title of my thesis is: “Shock Treatment: American Wartime Psychology and the Reeducation of Germany.” What does that mean? Here goes.

My thesis focuses on the period during and immediately after the Second World War. It analyzes a particular product of the American attempt, during the war, to understand how Hitler and the Nazi party had come to power in Germany and how the war had come about. While some American journalists, intellectuals, and government officials pondering this question turned to sociology, political science, or history for the answers, one group – the people I study – thought that psychology held the answers. At this point, you might be wondering how these people came to the conclusion that psychology, of all things, could provide the answers to the question at hand.

The short answer is that this group (which I named the “wartime psychologists”) believed, quite sincerely, that all nations had a definable “national character” – a set of traits constant throughout the population, despite differences in class, religion, political orientation, etc. – which shaped the “national mind,” a collection of attitudes, beliefs, and values, also assumed to be constant throughout the population. As a result, the American wartime psychologists were convinced that a singular “German mind” existed and that understanding what lay within this German mind would reveal why Germans had been attracted to the Nazis.

Given that the last decade and a half had seen the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party, as well as the fact that Nazi Germany was currently responsible for starting the Second World War and committing atrocities throughout Europe, these American analysts concluded that something had to be wrong with the German mind. But what? This is where psychology comes into the equation: the wartime psychologists believed that, by analyzing the German mind as a psychologist would analyze a patient, they could “diagnose” what, precisely, “afflicted” it. Furthermore, they believed they could “cure” Germany’s mental illness during the occupation period through a comprehensive program of reeducation.

These American “diagnoses” of the faults, or pathologies, of the German mind are the core of my thesis. Intrigued by the wartime psychologists’ beliefs and writings, I sought to understand what kind of attitudes these writings produced in the United States during and after the Second World War. Convinced that something was “wrong” with the German mind, the wartime psychologists had a sharply biased view of the nation and its people: one that caused them to play up Germany’s “deviancy” and to speak of Germany as a mentally ill nation.

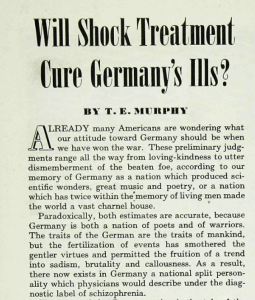

When I say that the wartime psychologists described Germany as a mentally ill nation, I don’t mean that they obliquely referred to it as such. On the contrary, they attempted to identify which mental illness, specifically, Germany was suffering from. For example, an American journalist writing in the Saturday Evening Post in 1944 argued that the conflicts and paradoxes inherent in the German mind had caused Germany to become schizophrenic. Because Germany was “both a nation of poets and of warriors,” he argued, “there now exists in Germany a national split personality which physicians would describe under the diagnostic label of schizophrenia.” Germany’s national psychological breakdown, he continued, “is the tale of the individual man multiplied several million times over … duplicated with monotonous regularity in every mental hospital in the world.” *

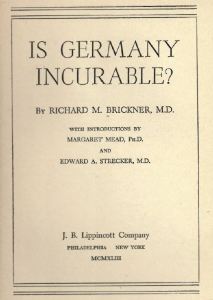

Amateur psychologists, such as the journalist quoted above, were not the only American analysts to describe Germany as a mentally ill nation and to attempt to diagnose its specific “malady.” A few professional psychologists and psychiatrists got involved, applying their clinical experience to the question of what was “wrong” with Germany. One psychiatrist, Richard M. Brickner, gained attention in the national press in 1943 for his book Is Germany Incurable?, which alleged that Germany, as a nation, suffered from “paranoia, as grim an ill as mind is heir to, the most difficult to treat, the only mental condition that frightens the psychiatrist himself.” Brickner insisted that he used the term paranoia as a “responsible medical diagnosis,” not an “epithet,” noting that he had arrived at the diagnosis of paranoia only after studying “the characteristic behavior of the German nation as a group. **

So: throughout the Second World War, a group of American analysts attempted to use psychology to uncover what lay within the “German mind,” an endeavor that ultimately ended with them concluding that Germany was a mentally ill nation and “diagnosing” its specific psychological pathologies.

Thinking about the long-term influence of the wartime psychologists’ conception of Germany as a mentally ill nation, I also sought to understand the consequences of their attempts to “diagnose” Germany’s psychological pathology. One thing I discovered was that the wartime psychologists’ analyses of Germany influenced the development of American occupation policy, particularly policies relating to German youth. Because the wartime psychologists had expended so much energy “diagnosing” Germany during the war – and because their theories had circulated throughout the American press – American occupation officials entered Germany in 1945 influenced by the wartime psychologists’ ideas.

What did this mean for the development of youth policy in occupied Germany? Before any sustained interaction with German youth, American occupation officials had preconceived notions of how young Germans would think and act. Influenced by the wartime psychologists’ arguments that Germany was a mentally ill nation, these officials believed that the minds of German youth had been “warped” (their words, not mine) simply by having grown up in Germany, which allegedly had an “abnormal” national mind.

American officials in occupied Germany believed that they had to “purge” young Germans’ minds of the “Nazi virus” (again, their words), fearing that if they failed to do so, German youth would never become democratic. Indeed, democratizing young Germans was a main goal of the American reeducation program, as they were the future of the country: if young people could not be democratized, there was little hope that Germany would remain democratic after the occupation. Accordingly, American officials sought to reorient young Germans’ minds: to excise, completely, National Socialist beliefs and values and, in their place, to implant democratic values and ways of living.

For a number of reasons, including American officials’ misjudging of young Germans’ psychological state and the widespread disillusionment of German youth, psychological change among young people happened slower than expected. Indeed, the final months of the war had shattered many young Germans’ belief in ideology, government, and even humanity. One young man interviewed in 1946 by a Saturday Evening Post correspondent said that his “world has collapsed like a tall chimney … now there’s nothing but a cloud of dust.” He remarked that he would “love to believe that this democracy everybody is talking about could be real someday,” but he was disillusioned by the “viciousness, jealousy, spite” that he observed in Germany at present, concluding that “the mean and the wicked rule supreme. Man is essentially evil; I’m convinced of it.” ***

Despite the slow start to the reeducation of German youth, by 1949, American officials had growing evidence that the minds of young Germans were being reoriented toward democracy. Increasing numbers of youth groups were organizing according to democratic principles and affirming a commitment to democracy – all signs that American efforts to teach German youth how to be democratic were beginning to pay off. Furthermore, American attempts to restore a sense of order and normalcy to the lives of young Germans, combined with material aid (especially the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949), demonstrated to German youth that democratic governments could improve the conditions of life in Germany. Essentially, the Americans “sold” democracy to young people. In 1949, the end result – the endurance of the democratic Federal Republic of Germany for nearly seventy years – was still contingent, but American officials found it increasingly realistic to hope, as a State Department report did in 1951, that German youth would soon have a “firm conviction that a democratic way of life offers richer satisfactions to the human mind and heart than any other way of life.”****

There you have it: the SparkNotes version of my thesis! If this discussion has made you interested in reading more about this topic, check out these books:

- Michaela Hoenicke Moore, Know Your Enemy: The American Debate on Nazism, 1933-1945 – a comprehensive study of the American attempt to understand Nazi Germany, with a discussion of the psychological approach.

- Petra Goedde, GIs and Germans: Culture, Gender, and Foreign Relations, 1945-1949 – discusses both American and German perceptions of each other and American reeducation programs in occupied Germany.

- Richard Bessel, Germany 1945: From War to Peace – my favorite general history of the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Allied occupation.

- James F. Tent, Mission on the Rhine: Re-education and Denazification in American Occupied Germany – a classic history of American reeducation policy during the occupation period (1945-1949).

Citations:

* T. E. Murphy, “Will Shock Treatment Cure Germany’s Ills?,” Saturday Evening Post, 1 January 1944, 76.

** Richard M. Brickner, Is Germany Incurable? (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1943), 30-33.

***Ernest O. Hauser, “The Germans Just Don’t Believe Us,” Saturday Evening Post, 3 August 1946, 18.

****U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, Young Germany: Apprentice to Democracy (1951), 78.

Leave a comment