This post was originally written in the summer of 2014, when I took a day trip to York while studying abroad in Cambridge, England. I am reposting it – slightly edited & with pictures added! – because I lived in York for six months (from fall 2019 to spring 2020, when the pandemic forced me to return home early) while studying for a master’s degree in cultural heritage management at the University of York. Enjoy this account of my first visit to York: little did I know at the time that, in five years, I would be living there!

After returning from my day trip to London last night (see account here), I woke up bright and early this morning to catch my train to York. Traveling from Cambridge to York required a stop in Peterborough, where Catherine of Aragon – Henry VIII’s first wife – is buried, though I did not have time to find the cathedral and do a bit of sightseeing. On the way from Peterborough to York, the train was slightly delayed due to signaling problems; the same thing happened when I returned to Peterborough in the evening. Other than the delays, the trip up to York wasn’t terribly memorable: a lot of flat farmland and wind farms.

Before traveling to York, I knew that it was an ancient Roman town, a Viking settlement, and an important medieval city, but I never realized that it had been a railroad hub in the nineteenth century as well. This new discovery was confirmed, first, by the sheer size of York’s train station and, second, by the fact that there is a memorial to the men of the railroads killed in World War I no more than two minutes from the train station. Also, I later learned that York is home to the National Railway Museum, though I didn’t have enough time to visit it.

Walking from the train station to the historic city center, I crossed the River Ouse, after which the spires of York Minster began to loom up in the distance. The Minster dominates the entire city center, visible from the city walls, two of the major gates into the city, and many of York’s streets. During my travels in Germany and Austria, I have been in many churches and cathedrals, some of which were impressive from the outside, others of which were impressive on the inside. None of them, however, can compare to York Minster, in my opinion.

Simply put, the Minster is the most massive church I have ever seen, as well as the most awe-inspiring in terms of size, architecture, and ornamentation. When I entered the church, the first part I saw was the nave, which actually looks as though it belongs in any ordinary Gothic church, due to its relative lack of ornamentation. One part of the nave that did stand out was the stained glass windows lining each wall. Indeed, the entire Minster has beautiful stained glass, from the two massive windows in the north and south transepts to the one in the east end (the front of the church) to the chapter house windows. As the east end window is currently being restored and is therefore not visible, there were interactive displays that allowed me to see the individual components of the window.

After learning about stained glass, I spent time being awed by the area around the Minster’s central tower. As its name suggests, the tower forms the middle (or very close to it) of the church’s floor plan, with the nave directly behind it and the quire directly in front; on either side, left and right, of the central tower, are the north and south transepts. This probably sounds quite confusing, but a glance at a floor plan of York Minster reveals that the church is in the shape of a cross, which is a common architectural characteristic of Gothic cathedrals. Both the north and south transepts have massive stained glass windows, and are enormous areas themselves, with small side chapels branching off of them.

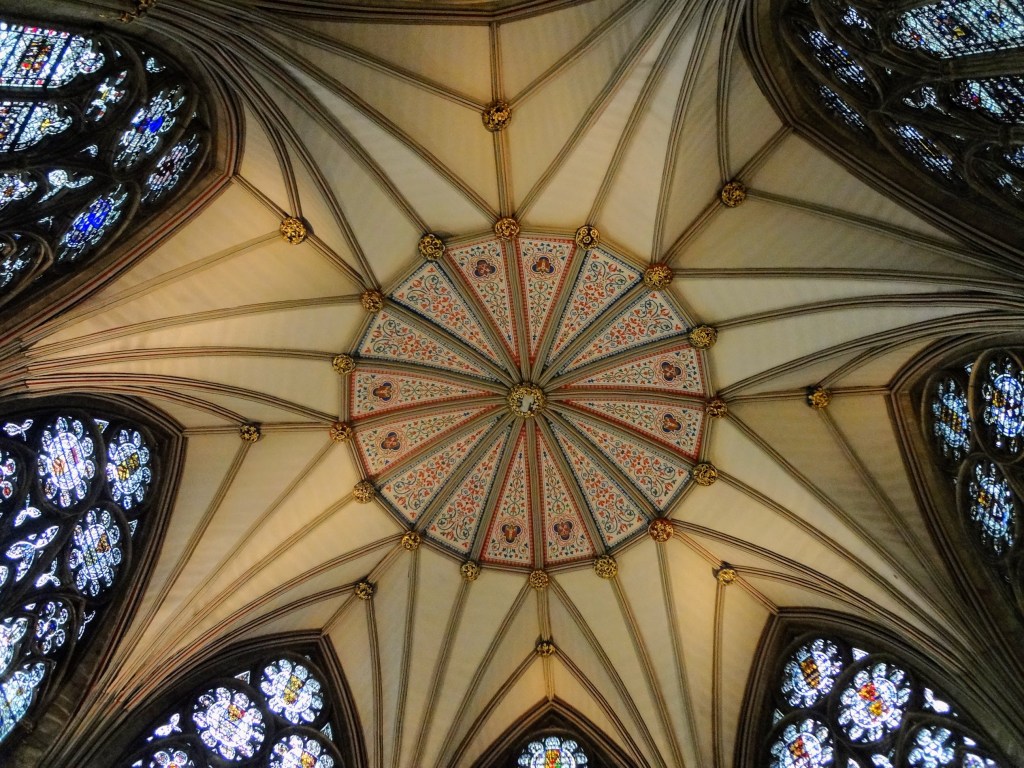

However, despite the magnificence of the transepts, my favorite part in this area of the Minster (probably my favorite part of the entire Minster) was the Kings’ Screen, which divides the nave, where ordinary people would have worshiped, from the quire, where monks and notables worshiped. This is no ordinary screen. Rather, it is a wall made up of statues of every English king from William the Conqueror to Henry VI, the king on the throne when the Minster was completed. I will write more about the Kings’ Screen later, as I studied it in great detail on my second visit to the Minster. For now, I will move onto the last main part of the Minster that I toured: the chapter house. You enter this part of the church from the north transept, down a hallway with more stained glass windows. The hallway then opens up onto the chapter house itself, which is octagonal, with a soaring roof not supported by any central column. While this is an impressive feat in its own right, I was most awestruck by the amount of stained glass in a relatively small space: each wall has a stained glass window. The sheer level of artistry and effort that went into creating all of the stained glass is absolutely amazing. Overall, I just do not have the right words to properly express my feelings about York Minster.

After spending over an hour in the Minster, I finally tore myself away and went in search of lunch, walking toward the Coppergate area, where the Jorvik Viking Centre is. Along the way, I walked through the Shambles, a medieval street famous for its overhanging buildings. That is, the street is so narrow that buildings on opposite sides of the street lean forward and very nearly touch. Seeing this made me realize just how crowded – and dark – medieval cities truly were, with people and vermin literally living on top of each other. No wonder that the plague, as well as other diseases, spread so quickly and with such devastating effect.

After lunch, I toured the Jorvik Viking Centre, which I was very intrigued to see, especially after learning about the effects that Viking raids, beginning in the late 8th century, had on Anglo-Saxon England. York itself is testament to the Vikings’ invasion of and settlement in England, as there was a Viking town (Jorvik) on the site of the modern city. After visiting Jorvik, I must confess that I was somewhat disappointed with the museum, as it was not as detailed as I would have liked with regard to Viking culture and society. I hoped to learn more about the structure of Viking society, their daily life, their customs, and their attitudes toward other peoples, such as the Anglo-Saxons. However, the museum’s exhibitions focus on the archaeological excavations in York, which took place on the site of the Viking Centre today, and on the artifacts discovered there. Despite my disappointment with the focus of the exhibitions, visiting Jorvik was very interesting from a public history standpoint, given that a large part of museum is comprised of a motorized ride through a recreation of the Viking town of Jorvik. The recreation included houses, shops, people, animals, objects relating to material culture, and even smells. It was obviously designed to immerse visitors in Viking-era York, especially as it was accompanied by an audio explanation of what we were hearing and seeing. The idea of making a museum more like a multimedia presentation was very intriguing, and something that I had not seen in a museum before.

Note: at the time, I thought that the display was a bit pedestrian, but now (five years later), after visiting Jorvik again, I can say that I truly enjoyed my visit. I appreciate the work – in terms of research, interpretation, construction, and presentation – that the Viking Centre put into the recreation of Jorvik. I also now realize that, for people with no previous knowledge about Viking culture, society, and life, the recreation is an excellent way to make history accessible and enjoyable: to draw visitors in and get them interested in Viking history, by allowing them to “experience” it for themselves.

As I was leaving Jorvik, the sky opened up, and it began to pour, which it proceeded to do for most of the rest of the afternoon. Nevertheless, as I was determined not to let the rain spoil my day in York, I set off to walk the city walls and visit two museums located in former city gates: the Henry VII Experience in Micklegate Bar and the Richard III Experience in Monk Bar. Why are there museums dedicated to these two kings in York? In the second half of the 1400s, two branches of the English royal family – the Yorkists and the Lancastrians – fought for control of the throne. York, as you might have guessed, was the stronghold of the Yorkists, who took as their symbol the white rose. Because the Lancastrians’ symbol was the red rose, the decades-long conflict is remembered as the Wars of the Roses. Richard III was the final Yorkist king, ruling from 1483 to 1485, when he was defeated in battle by Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian claimant to the throne. Seeking to end the conflict (and retain the throne), Henry – now Henry VII – married Elizabeth of York, Richard’s niece, thus uniting the two branches once more. He also united the symbols of the two branches: the Tudor rose had a white center and a red border.

York has probably the most intact city walls of any city in England, initially constructed by the Romans and altered throughout the years by subsequent rulers of England. After visiting the Henry VII museum in Micklegate Bar, I walked the walls to Monk Bar, home of the Richard III museum. Of the two, I found the Richard III museum to be more interesting, partially because Richard is a much more controversial figure. To this day, historians debate how personally involved Richard was in the disappearance of his nephews (the so-called Princes in the Tower), the event which enabled him to take the throne. Shakespeare famously portrayed Richard as a hunchback and an outsider, who fought back by plotting to take the throne and other villainous activities. It is important to remember, though, that Shakespeare’s history plays were always partially fictionalized and that he wrote during the reign of the Tudors: it wouldn’t do to praise the Tudors’ predecessors too much!

By the time that I left Monk Bar, it was truly pouring and quite unpleasant outside, so I headed back to York Minster, as my ticket gave me unlimited access for twelve months. The church was just as impressive on my second visit, and somewhat less crowded, allowing me to make a detailed study of the Kings’ Screen. After looking at each statue closely, especially those of the later Plantagenets – Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI – I came to the conclusion that the statues reflect the kings’ personalities to a remarkable degree. For instance, unlike most of the others, the statue of Henry III bears no sword, as Henry was not a warlike king.

Edward I, on the other hand, holds a sword in one hand and makes a fist with his other hand, as befits his warlike tendencies and nickname: “Hammer of the Scots.” By his side, his son Edward II is the complete opposite, holding no sword, and looking at his hand as if trying to understand where he went wrong. This is very true to life, as Edward II was a weak king, eventually overthrown by his wife and her lover, and brutally murdered in 1327. The last Edward portrayed, Edward III, reflects more of the spirit of Edward I. Although he holds no sword, Edward III appears powerful, holding a rod of state to reflect the changes in English politics during his reign, such as the introduction of English as the official language of the nation (replacing French). Additionally, he looks out in the distance, as if he is surveying his campaigns in France during the Hundred Years’ War.

The best part of returning to York Minster was that I was able to catch the end of a choral and organ service, which was absolutely beautiful. Something about the choir singing and the organ playing made the Minster seem even more beautiful, majestic, magnificent, and magical than before. The music accentuated the soaring quality of the Gothic architecture, drawing my eye up higher and higher, as was undoubtedly the object of the builders: to have architecture bring one closer to God. As I exited the Minster for the last time, it worked one last miracle (if that is the right word), as the rain had stopped, the clouds had disappeared, and the sun was shining over the Minster, allowing me to perceive it as it should be seen. Unfortunately, I had to leave soon after to catch my train back to Cambridge. Aside from the weather, I am very glad that I chose to spend the day exploring York.

Final note: I loved living in York, and I’m patiently waiting for the day when I can go back!

Leave a comment