A few weeks ago, I was in the Nashville area to visit a friend, and I decided to add a day on to my trip in order to visit Stones River National Battlefield in Murfreesboro. Over the years, I’ve visited many of the Tennessee Civil War battlefields, including Shiloh, Chattanooga, and Knoxville. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, I lived on what was once the Fort Sanders battlefield; there was even a Civil War battlefield monument right beside one of my dorms. Despite all of this exploring, however, I hadn’t yet made it to Stones River – until now.

The Battle of Stones River took place from December 31, 1862 to January 2, 1863. It was fought between the Union Army of the Cumberland, under the command of Major General William Rosecrans, and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under the command of General Braxton Bragg. The two armies met in Murfreesboro and fought for control of the Nashville Pike, the main Union supply and communications artery in Middle Tennessee. After several days of hard fighting, the Union had won the battle, retaining control of the Nashville Pike. The Confederate army retreated further south, toward Chattanooga, losing much of its territory in Middle Tennessee. A few days later, the Union army marched into Murfreesboro. President Abraham Lincoln, who desperately wanted a Union victory to support his newly-issued Emancipation Proclamation, was relieved to hear the news of the Union success at Stones River. Lincoln later wrote to Rosecrans that he had delivered the Union “a hard earned victory.”

Stones River National Battlefield was first established as Stones River National Military Park in 1927; it was redesignated a national battlefield in 1960. It preserves a large section of the original Stones River battlefield and includes Stones River National Cemetery, established in 1864.

For me, visiting a battlefield – any battlefield, not just a Civil War battlefield – places you in the role of detective. Using the information given, such as the topography, landmarks mentioned in soldiers’ accounts, maps of the battlefield, and the history of the battle, you, as the visitor, try to reconstruct what happened, many years after the battle occurred. Where were the opposing armies? Which direction did soldiers move? What was the object of the battle? Why was the battle fought on this particular ground?

Some battlefields are easy to decode: the topography spells out what happened on this ground. Gettysburg is a good example of this, as the battlefield has very distinct terrain. As you follow the tour route around the Gettysburg battlefield, you can easily understand what happened during the battle by surveying the hills and ridges where the battle took place. You can see where the Union lines were, what the Confederates were trying to achieve by attacking in particular places, and how the battle was shaped by topography.

Other battlefields are a bit harder to “read.” Stones River, for me, is one of these. It wasn’t until the third or fourth stop on the tour route that I truly began to understand what happened at the Battle of Stones River. The battlefield is very flat, as you can see from the image above, which makes it harder to visualize where the Union and Confederate lines were. However, once I reached the Cotton Field and was able to orient myself in relation to the objective of the battle – the Nashville Pike – everything started to make sense. It took a bit more work, but in the end, my battlefield “detective skills” came through, and I left Stones River feeling that I understood the battle.

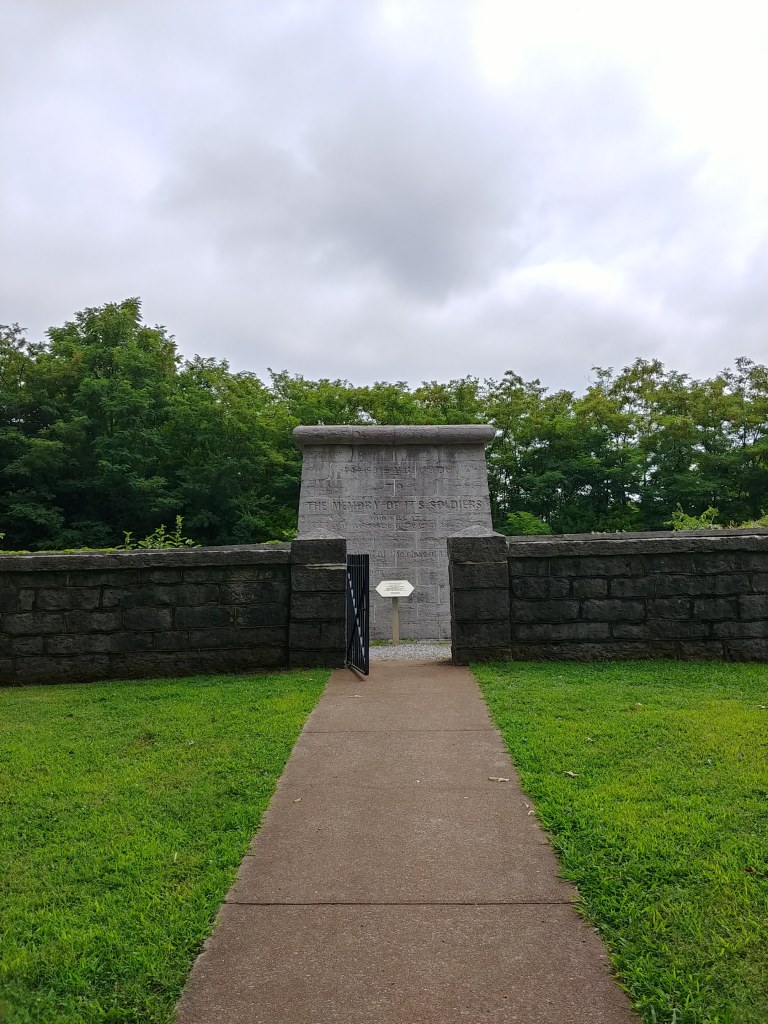

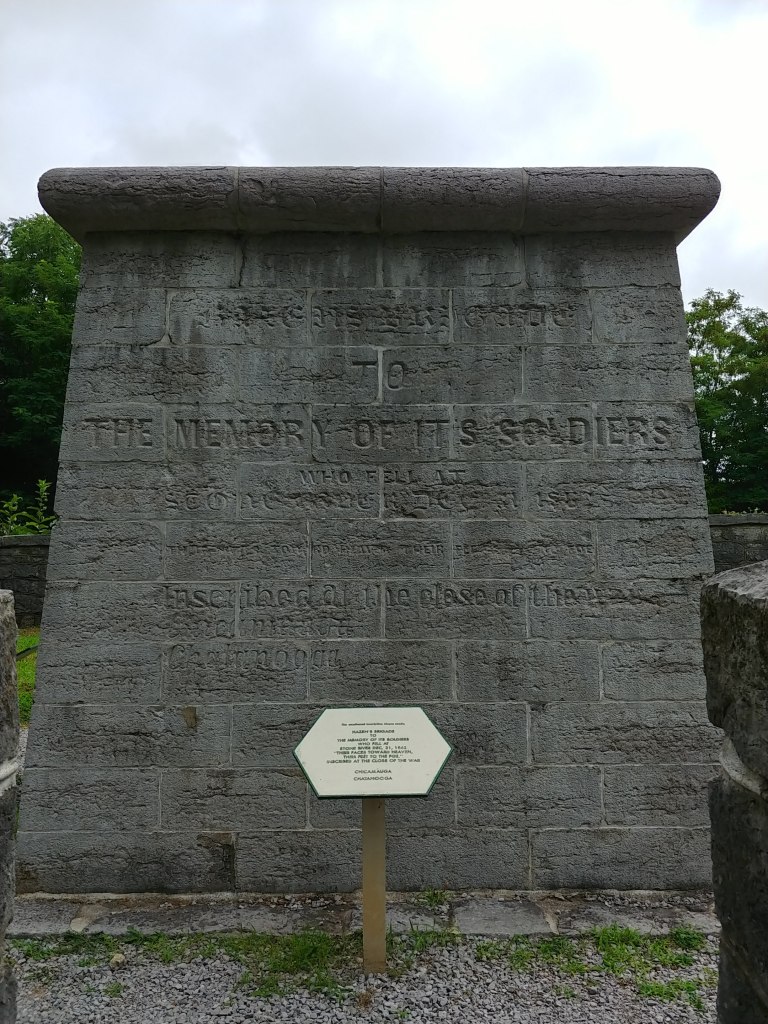

Two locations at Stones River were particularly interesting for me: the Hazen Brigade Monument and the Stones River National Cemetery. The Hazen Brigade Monument is the oldest intact Civil War monument in the country. Built in 1863, two years before the war ended, it commemorates the fallen soldiers of a Union brigade – the only Union unit to hold its ground without retreating on the first day of the battle.

The monument is much simpler in style than later Civil War monuments, whether Union or Confederate, which often are very elaborate. In a way, though, the Hazen Brigade Monument is more poignant than those later monuments, as the men it commemorates are buried around the monument, their gravestones worn down by time. This monument was not constructed as part of a post-war narrative of “Lost Cause” or glorious sacrifice for the nation. It was built by the comrades of the fallen, at a time when the ultimate outcome of the war was still very much in doubt.

I also found the Stones River National Cemetery very interesting. Following the Battle of Stones River, most of the Union and Confederate dead were quickly buried where they lay on the battlefield. After the war ended, the Union dead were disinterred and reburied in Stones River National Cemetery, which had been established in 1864 by order of Union general George H. Thomas. The Confederate dead, who were not eligible for burial in the national cemetery, were reburied at public cemeteries in Murfreesboro or in their home towns. Between October 1865 and the end of 1866, more than 6,000 Union soldiers were reburied at Stones River National Cemetery. Much of the work of disinterment and reburial was done by soldiers of the 111th United States Colored Infantry.

As I walked through Stones River National Cemetery, one of the things that struck me was the regularity of the burials, which you can see in the pictures above. The graves are not haphazard; they are set in lines which form a pattern: each section of graves appears to radiate out from a central point. This point stood out to me, because I’ve seen this arrangement of graves at American military cemeteries before, in Europe. For example, the graves at the Luxembourg American Cemetery, where many American soldiers who were killed in the Battle of the Bulge are buried, are arranged in a very similar pattern.

It wasn’t until I visited Stones River that I realized that Civil War cemeteries – at least those created by the Union army – clearly set a pattern for the design of American military cemeteries, one that was followed as military cemeteries were created in Europe after the First and Second World Wars.

My visit to Stones River National Battlefield gave me much to reflect (and write) on. I’m very glad that I finally took the time to visit this battlefield. After visiting Stones River, the only major (preserved) Tennessee Civil War battlefield that I haven’t visited is Fort Donelson National Battlefield. I’ll have to add that to my list.

Leave a comment