For anyone interested in German history, 2023 will be a year of anniversaries, as this year marks the centenary of three significant events in modern German history: the occupation of the Ruhr industrial area by French and Belgian soldiers, intended to force Germany to pay its reparations; the resulting hyperinflation and complete devaluation of Germany’s currency; and the Beer Hall Putsch, Adolf Hitler’s first attempt to seize power. Each of these events tested the stability of the democratic Weimar Republic, which had been beset by political, economic, and social turmoil since its establishment in November 1918. While the Weimar Republic was able to overcome the challenges of 1923 in the short term, the events of this year would have significant long-term effects for German politics and society. To understand the ramifications of what happened a century ago in Germany, let’s take a look at the major events of 1923.

The occupation of the Ruhr: On January 11, 1923, French and Belgian soldiers entered and occupied the Ruhr industrial area in western Germany in an attempt to force the German government to make its reparations payments, as stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles. Two years previously, in 1921, the victorious Allies had set the total amount of reparations that Germany had to pay at approximately $31 billion (which is well over $400 billion today). Germany, already weakened economically by World War I, could not afford the massive reparations payments required of it. At the same time, France, also suffering from the economic aftereffects of the war and needing to pay back wartime loans from the United States, depended on German reparations payments to stabilize its economy. When Germany defaulted once again on its reparations payments at the end of 1922, France (and Belgium also) decided to occupy the Ruhr, Germany’s main industrial area, in order to force Germany to pay up. Britain, the other major Allied power, refused to participate in the occupation of the Ruhr, partially because the British government feared that the occupation of the Ruhr would further weaken the German economy and partially because British leaders did not want France to become the dominating power on the European continent.

When French and Belgian troops entered the Ruhr on January 11, 1923, the German population in the area responded with a campaign of passive resistance. Workers in the coal mines and factories of the Ruhr refused to work for the French and Belgian occupiers; this passive resistance was financed by the German government. The occupation of the Ruhr was thus a major (though perhaps not the only) cause of the second major event of 1923 in Germany: the near-complete collapse of the German economy due to hyperinflation.

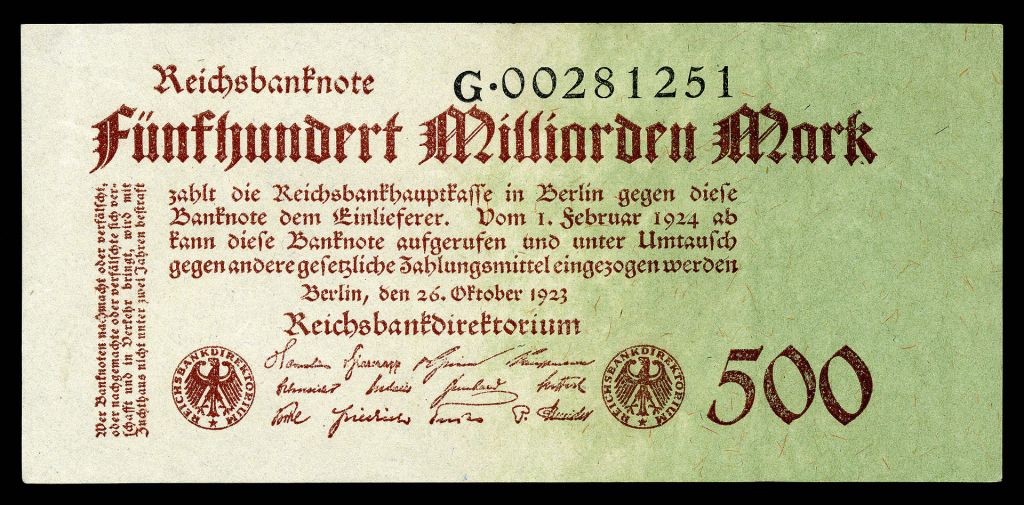

Hyperinflation: The occupation of the Ruhr and the German campaign of passive resistance put further strain on the already-strained German economy. Ever since the end of World War I, inflation had been rampant in Germany as the effects of wartime debt and postwar reparations payments led to an increasing devaluation of the German mark. However, the event that transformed this inflation into a rapid hyperinflation, leading to massive economic collapse, was the occupation of the Ruhr. As mentioned above, the German government decided to finance German workers’ passive resistance in the Ruhr. In order to do this, the German government printed more and more money, leading to massive hyperinflation. The hyperinflation in Germany in 1923 is hard to comprehend, even in the context of inflation and rising prices today. By November 1923, one U.S. dollar was worth around 4.2 trillion (yes, trillion) German marks. Inflation accelerated so rapidly that sometimes banknotes were re-stamped with a new value, rather than printing an entirely new note, enabling a billion-mark note, for example, to quickly become a trillion-mark note.

The hyperinflation in 1923 had major effects on German society. Many people lost their entire life savings as their money became worthless quite literally overnight. The two major beneficiaries of the hyperinflation were people who owned property, the value of which did not depreciate, and people in debt, who could pay off their debt with increasingly worthless money. Everyone else in Germany suffered. Stories abound of people papering their walls with banknotes, which had more value to them as wallpaper than as money, or people taking wheelbarrows full of money to the market to buy food. Sometimes people would steal the wheelbarrow (which had value) and leave behind the money.

The combination of the occupation of the Ruhr and the hyperinflation threw the Weimar Republic, no stranger to crisis, into chaos. Having survived an attempted communist uprising in 1919 (the Spartacist uprising), an attempted nationalist-monarchist coup in 1920 (the Kapp putsch), and the assassination of Walther Rathenau, the foreign minister, by a right-wing paramilitary group in 1922, the Weimar Republic faced further challenges to its existence in 1923. As the peak of the hyperinflation hit in the fall of 1923, several groups of varying political persuasions attempted coups against the Weimar Republic. In the Rhineland, some political leaders entered into talks with France, hoping to form a Rhenish republic in economic union with France in order to save the Rhineland’s economy. One person associated with these talks was Konrad Adenauer, the mayor of Cologne, a leading Catholic politician in the Rhineland. While becoming associated with Rhenish separatism did not help Adenauer’s political career in the Weimar Republic, it ultimately proved beneficial, as Adenauer, relatively untarred by the failure of the Weimar Republic and staunchly anti-Nazi, became the first chancellor of West Germany in 1949.

Another group that attempted a coup against the Weimar Republic in the fall of 1923 was a relatively little-known right-wing party, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, led by a World War I veteran named Adolf Hitler. In November 1923, Hitler and the Nazi Party attempted to seize power in Munich, in what has become remembered as the Beer Hall Putsch.

The Beer Hall Putsch: The economic and political turmoil caused by the occupation of the Ruhr and the hyperinflation convinced Hitler and his political allies in Munich, who included the prominent World War I general Erich Ludendorff, that the time was right to seize power, first in Bavaria (of which Munich was the capital) and then in Germany as a whole. Hitler’s planning for his coup was inspired by Benito Mussolini’s successful March on Rome in October 1922, which brought the Fascist Party to power in Italy. Indeed, Hitler planned to seize power in Munich, then gather his followers and march on Berlin, the national capital, to overthrow the Weimar government. Hitler set his plan in motion on the night of November 8, 1923. Accompanied by his top associates, including Hermann Goering, and a large group of men from the SA (Sturmabteilung, or Storm Troopers, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party), Hitler interrupted a political meeting of Bavarian government officials at the Bürgerbräukeller (a beer hall) in Munich. Hitler and the Nazis seized several prominent Bavarian officials, including Gustav Ritter von Kahr, the head of the Bavarian government, and forced them to support Hitler’s proclamation of a national revolution. However, as soon the officials were released, they hurried to rally Bavarian government forces to oppose Hitler’s coup.

Confusion reigned throughout the night, as Bavarian officials and police and military leaders tried to figure out (a) what was going on and (b) what side they wanted to support. By the morning of November 9, it was becoming increasingly clear to Hitler that his putsch attempt was failing. As a final step, Hitler and Ludendorff decided to march with their supporters through the streets of Munich. As Hitler and the Nazis marched into Odeonsplatz in central Munich, they were met in front of the Feldherrnhalle by a force of Bavarian soldiers and police, who opened fire. In the resulting fighting, fourteen Nazis and four police officers were killed; one of the Nazis killed was Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, a close associate of Hitler, who was walking arm-in-arm with Hitler when he was shot. Ludendorff and Hitler, who had been injured, fled the scene, but were arrested later. Goering managed to escape to Austria, but he had been injured in the fighting, an injury that led to his morphine addiction.

In the aftermath of what became known as the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler and his top associates, including Ludendorff, were charged with treason and put on trial. Hitler used the trial as a platform through which to spread his political message; because the trial was reported in national newspapers, Hitler’s ideas received national attention for the first time. Ludendorff, probably largely due to his status as a hero of World War I, was acquitted at trial. Hitler was convicted of treason and sentenced to five years in prison; he actually served about nine months at Landsberg prison, during which time he wrote Mein Kampf, his political manifesto. Upon his release from prison in December 1924, Hitler vowed to rebuild the Nazi Party and decided that, next time, he would gain power legally, by working within the system.

As a postscript, in June 1934, Hitler had Gustav von Kahr, who he blamed for the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch, killed during the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler’s purge of the SA and other potential political opponents.

Stabilization: The failure of the Beer Hall Putsch coincided with the beginning of the stabilization of the German economy. In September 1923, the new German chancellor, Gustav Stresemann, a monarchist-turned-democrat and profoundly pragmatic politician, announced the end of passive resistance in the Ruhr. At the same time, the German president, Friedrich Ebert, announced a state of emergency, which would last until February 1924. Stresemann also sought to bring the hyperinflation under control; as a result, a new German currency, the Rentenmark, was introduced in November 1923. The introduction of the new currency began to bring inflation under control and stabilized prices within Germany.

While these measures stabilized the situation in Germany in the short term, Stresemann understood that the only way to stabilize the German economy – and thus the political situation – in the long term was to reach an agreement with the Allied powers on reparations payments. The Allies and Germany reached just such an agreement in August 1924, by which time Stresemann had lost the position of chancellor, though he stayed on as foreign minister until his death in 1929. The Dawes Plan, named for Charles G. Dawes, the American banker who led the committee that developed it, provided for an end to the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr and introduced a staggered payment plan for Germany’s reparations payments. Under the terms of the Dawes Plan, American banks loaned Germany money to help it meet reparations payments.

The short-term effect of the Dawes Plan was as hoped: in 1925, France and Belgium withdrew their troops from the Ruhr, and the German economy stabilized, beginning a period known as the “golden age of the Weimar Republic” (1924-1929). However, a circle of debt had been established: American banks loaned money to Germany, which then paid reparations to France, Britain, and the other Allied powers; these countries in turn used the reparations money to repay their own debts to the United States. Although effective in the short term, this arrangement would be thrown into chaos by the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, when American banks cut off payments to Germany, which threw the German economy into deep economic depression. The economic, social, and political impact of the Great Depression in Germany can hardly be understated, as it led to a collapse of the democratic government and the rise of extremist parties, one of which would be successful in achieving power in January 1933. A little less than ten years after the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler would gain power legally in Germany.

As this brief survey of events has revealed, 1923 was a highly significant year in German history, as events tested the stability of the Weimar Republic and set in motion forces that, when combined with subsequent events, would in the end bring down the Weimar Republic.

Leave a comment