Traces of the past are everywhere in Berlin. The city is dotted with memorials, monuments, and plaques that mark significant events and commemorate important figures in German history. Many of these memorials only hint at the larger history behind them. This is especially true for two memorials located on the western edge of the Tiergarten, a large park in central Berlin. Located a few hundred meters apart, each of these memorials is composed of a plaque, providing historical information, and the actual memorial. So why were these memorials erected in these locations? And, more importantly, who do they memorialize?

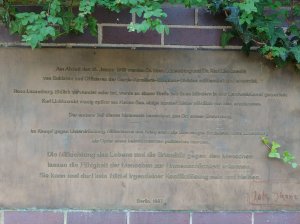

Each of these memorials marks the spot where a prominent German communist leader was killed – or where their body was dumped – in the aftermath of a failed communist uprising in January 1919. Located on the shore of the Neuer See, one memorial indicates the place where members of a Freikorps unit (the Freikorps were conservative paramilitary groups founded in the aftermath of World War I) shot Karl Liebknecht. A few hundred meters south, the second memorial marks the site where the same Freikorps unit threw the body of Rosa Luxemburg into the Landwehr Canal.

Although their names are not as well known today as those of the leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were prominent leaders of the communist movement in Germany in the early twentieth century. Liebknecht came from a leading German socialist family. His father, Wilhelm Liebknecht, was one of the founders of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), established in 1863, seven years before the unification of Germany. Karl Liebknecht followed in his father’s footsteps, studying law and joining the SPD; in 1912, Liebknecht was elected to the Reichstag as a representative of the SPD. (Interestingly, in this election the SPD became the largest party in the Reichstag, and it remained so when World War I broke out in 1914.)

While Rosa Luxemburg is closely associated with the socialist movement in Germany, she was born to a Polish Jewish family in Zamość, then part of the Russian Empire (now in Poland). Becoming involved in left-wing politics at an early age, Luxemburg fled Russia for Switzerland in 1889 in order to avoid arrest by the tsarist police, who monitored the activity of all radical political groups. Once in Switzerland, Luxemburg studied philosophy, history, politics, economics, and mathematics at the University of Zurich. In 1897, she earned a doctoral degree from the University of Zurich, with a dissertation on the industrial development of Poland. Aside from a brief return to Russia during the 1905 Revolution, Luxemburg lived in Germany for much of her adult life, having married the son of an old friend in 1897 in order to obtain German citizenship. In the years before World War I, Luxemburg was active in the left wing of the SPD; a close associate and friend was Clara Zetkin, a prominent German female socialist activist.

When World War I began, Luxemburg, Liebknecht, Zetkin, and other members of the SPD’s left wing were adamantly opposed to the war and, especially, the decision of the majority of SPD delegates in the Reichstag to approve funding for the war. As a result, Luxemburg and Liebknecht broke with the SPD, founding the International Group (renamed the Spartacus League in 1916). Because of their political activities, particularly writing and distributing anti-war pamphlets, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were imprisoned in June 1916, although Luxemburg continued to write articles, which were smuggled out of prison and published. In October 1918, Liebknecht was released from prison as part of a general amnesty; a few weeks later, in early November 1918, Luxemburg was also released from prison. On November 9, 1918, just hours after the SPD politician Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a German republic following the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II, Liebknecht proclaimed a socialist republic from a balcony of the Berlin Palace. In the following weeks, Luxemburg and Liebknecht reorganized the Spartacus League, which became part of the new Communist Party of Germany (KPD), founded on January 1, 1919.

Soon afterwards, on January 5, 1919, in an attempt to make Liebknecht’s proclaimed socialist republic a reality in Germany, the Spartacists launched an uprising in Berlin. Their goal was to overthrow the provisional government of Germany, which was led by moderate social democrats in the SPD, and replace it with a council-style republic, similar to that initially established by the Bolsheviks in Russia. Liebknecht was more in favor of the uprising than Luxemburg, who – correctly, as it turned out – feared that armed insurrection was a blunder. In the end, the Spartacist Uprising, as it came to be known, was short-lived. After around a week of street fighting in Berlin, the uprising was crushed by the Freikorps (the conservative paramilitary forces) on the orders of SPD leader and de facto head of government Friedrich Ebert. Ebert’s actions have ever after been controversial, as Ebert, himself a social democrat, allied with the conservative, nationalist Freikorps in order to suppress other leftists. However, Ebert found himself in an extremely difficult situation, given the chaotic political situation in Germany in the months after the end of World War I. His decision to focus on restoring order, whatever the cost, must be seen in the context of the civil war, general disorder, and fearing of a spreading Bolshevik revolution sweeping Germany at the time.

After the failure of the Spartacist Uprising, Luxemburg and Liebknecht went into hiding, realizing that their lives were in danger. Three days after the end of the uprising, on January 15, 1919, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were captured by members of a Freikorps unit while hiding at an apartment in the Wilmersdorf neighborhood of Berlin. No one knows who informed the Freikorps about to Luxemburg’s and Liebknecht’s whereabouts. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were questioned under torture by the Freikorps unit, the leader of which made the decision to summarily execute the two of them. As mentioned at the beginning of this post, Liebknecht was shot near the Neuer See in the Tiergarten; his body was brought to a morgue without identification. Luxemburg was shot, and her body was thrown into the Landwehr Canal, near the spot where her memorial now stands. Several months later, in June 1919, a body believed to be Luxemburg’s was recovered from the Landwehr Canal. Her remains and those of Liebknecht were buried in the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery in Berlin, the resting place of many German socialists and communists, including Wilhelm Liebknecht.

In 1926, a large memorial designed by modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was erected at the Friedrichsfelde cemetery to commemorate Luxemburg, Liebknecht, and other communist fighters who died during the Spartacist Uprising and other events in 1919 and 1920. The memorial was demolished by the Nazis in 1935 and never rebuilt, even though the cemetery ended up in communist-ruled East Berlin after World War II. In the late 1980s, the memorials to Luxemburg and Liebknecht in the Tiergarten were erected; somewhat ironically, both sites were located in West Berlin at the time.

After 1949, East German leaders, many of whom had been members of the KPD in the 1920s, idolized Luxemburg and Liebknecht as martyrs for the socialist cause. When the ruins of the Berlin Palace were demolished in 1950 on the orders of East German leader Walter Ulbricht, the “Liebknecht balcony” (where Liebknecht had proclaimed a socialist republic in November 1918) was preserved and incorporated into the State Council Building. Furthermore, many places in East Berlin were named after Luxemburg and Liebknecht, including Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz in the Mitte district. Following the collapse of East Germany in 1989, some of these places were renamed, but many kept their names (unlike places named after East German leaders), as Luxemburg and Liebknecht were considered to be significant historical figures, not “tainted” by association with East Germany.

As has become clear throughout this post, there is a long, complex history behind the memorials to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in the Tiergarten. In Berlin, where the past is ever-present, you never know when you may stumble across a memorial – and you never know how much you might learn if you stop to investigate the history behind a monument.

Leave a comment