York Minster dominates the cityscape of York, one of the oldest and most historically important cities in northern England. Founded by Romans, settled by Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, a center of power in the medieval period, and a city of enduring economic importance, York is well-worth a visit. Regular readers of this blog will know that York has a special place in my heart, as I lived there for six months and have visited on several other occasions. While there are many fascinating museums, heritage sites, cafes, and so on to visit in York, no trip to York is complete without a visit to York Minster. One of England’s great cathedrals, along with Canterbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, York Minster has a long and rich history and is a wonderful example of English Gothic architecture.

There may have been Christians in York in Roman times (when the city was known as Eboracum), especially after Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in 313 CE. However, evidence for the practice of Christianity in Eboracum, particularly in terms of the construction of churches, is very limited. As such, the first church known to have been constructed in York dates to the Anglo-Saxon period. In 627, a wooden church was built in York for Edwin, King of Northumbria, who had decided to convert to Christianity. The church was hastily constructed in order to host Edwin’s baptism. Soon afterwards, it was decided to replace the wooden church with a more permanent stone church, which was completed 10 years later, in 637. No archaeological evidence of the Anglo-Saxon minster has ever been found, so historians have very little idea what it would have looked like.

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, William the Conqueror sought to use York to project Norman military and spiritual power in the restive north of England. Following the brutal pacification of northern England, known as the Harrying of the North, Norman officials in York embarked on a two-pronged building project to cement their control of the city – and the north. On one end of the city, the construction of York Castle began, a physical manifestation of Norman military and political power. At the other end of the city, beginning in 1080, the Anglo-Saxon minster was replaced by a much larger cathedral constructed in the Romanesque style brought to England by the Normans. This architectural style is characterized by rounded arches, large columns, and small, high windows.

In the 13th century, a new architectural style swept across western Europe: Gothic architecture. In 1220, the Archbishop of York, Walter de Gray, initiated a massive renovation and expansion of York Minster, which would transform the Norman minster, bit by bit, into a magnificent Gothic cathedral. Gothic architecture combines a number of technological innovations, including soaring vaulting, pointed arches, and flying buttresses, all designed to support the enormous weight of the cathedral. Another feature of Gothic architecture was massive stained-glass windows, which let light flood into the cathedral and were intended to draw worshippers’ eyes up toward heaven. The transformation of York Minster into a Gothic cathedral took centuries. Indeed, when Edward III married Philippa of Hainault at York Minster in 1328, the cathedral was still under construction. Building work would continue until 1472, when the construction was finally declared done, and the minster was consecrated.

As was the case with churches and cathedrals all over England, York Minster was not spared the impact of the English Reformation, particularly Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. Many of the Minster’s treasures were looted during the Reformation, and tombs and altars inside the cathedral were destroyed in an effort to remove any trace of Catholicism. A century later, during the English Civil War, the city of York was besieged by – and fell to – Parliamentary forces. However, York Minster was spared damage by the intervention of the Parliamentary commander, Thomas Fairfax, who was from Yorkshire. Fairfax ensured that the Minster was not looted or damaged by his troops after the capture of York.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, an effort was made to restore York Minster. However, this restoration work was undone in the following decades by two major fires. An arson attack on the Minster in 1829 inflicted heavy damage on the quire, central aisle, and east side of the building. Another fire in 1840, this one accidental, severely damaged the Minster again. For several years afterward, York Minster’s future looked bleak: the cathedral was heavily in debt, and services were suspended. However, beginning in the late 1850s, the Dean of York, Augustus Duncombe, sought – successfully – to revive the Minster.

More threats to the Minster developed in the 20th century. In 1916, after a German Zeppelin raid on York, the Minster’s stained glass windows were removed for safekeeping. During World War II, the windows were removed yet again to prevent them from being destroyed in a bombing raid. While York Minster avoided destruction during the World Wars, a serious threat to the cathedral’s future emerged in the late 1960s. In 1967, a building survey revealed that the Minster’s central tower was in serious, immediate danger of collapsing. A collapse of the central tower would have been devastating to the Minster, not to mention the damage inflicted on surrounding buildings, as well as the loss of a cultural heritage treasure. To save York Minster, authorities undertook a £2 million project to reinforce the Minster’s foundations and repair damage to the building’s stonework. During excavations to prepare the way for steel cables to be inserted into the foundations (to quite literally keep the cathedral together), an earlier chapter of the site’s history was revealed. The construction team unearthed the remains of the north corner of the Roman principia (military headquarters) that once stood in Eboracum. Today, visitors to York Minster can view the Roman remains in the Minster’s undercroft, which features an exhibition on the history of York Minster; remains of the Norman minster can be seen in the crypt.

No sooner had the York Minster’s collapse been averted than another crisis in the cathedral’s history occurred. In 1984, a major fire, likely caused by a lightning strike, broke out in the South Transept. While the Minster incurred serious damage, the actions of firefighters prevented a worse tragedy. By deliberately collapsing the roof of the South Transept, the rest of the Minster was saved from destruction; additionally, firefighters were able to save the South Transept’s rose window, a beautiful example of medieval stained glass. Following the fire, the rose window and the South Transept were restored, with construction completed in 1988. In the decades since, York Minster has not suffered any further damage, but conservation work on the Minster is almost constant. A massive conservation project on the Great East Window was completed in 2018, and an equally massive restoration of the Minster’s organ was completed in 2021. Conservation projects such as these will keep York Minster standing for centuries to come, ensuring that many more generations will be able to worship here and be awed by the cathedral’s magnificent architecture.

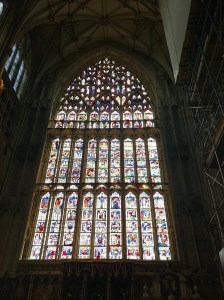

No discussion of York Minster is complete without highlighting a few notable features of the Minster. While the Minster has an amazing array of medieval stained glass, the Great East Window is one of the most magnificent examples of stained glass in the cathedral. In fact, it is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in England. Created in the 15th century, the Great East Window depicts scenes from the Book of Revelation.

One of my favorite parts of York Minster is the chapter house, where monks and other church officials would meet in the medieval period. Octagonal in shape, the chapter house has an amazing ceiling.

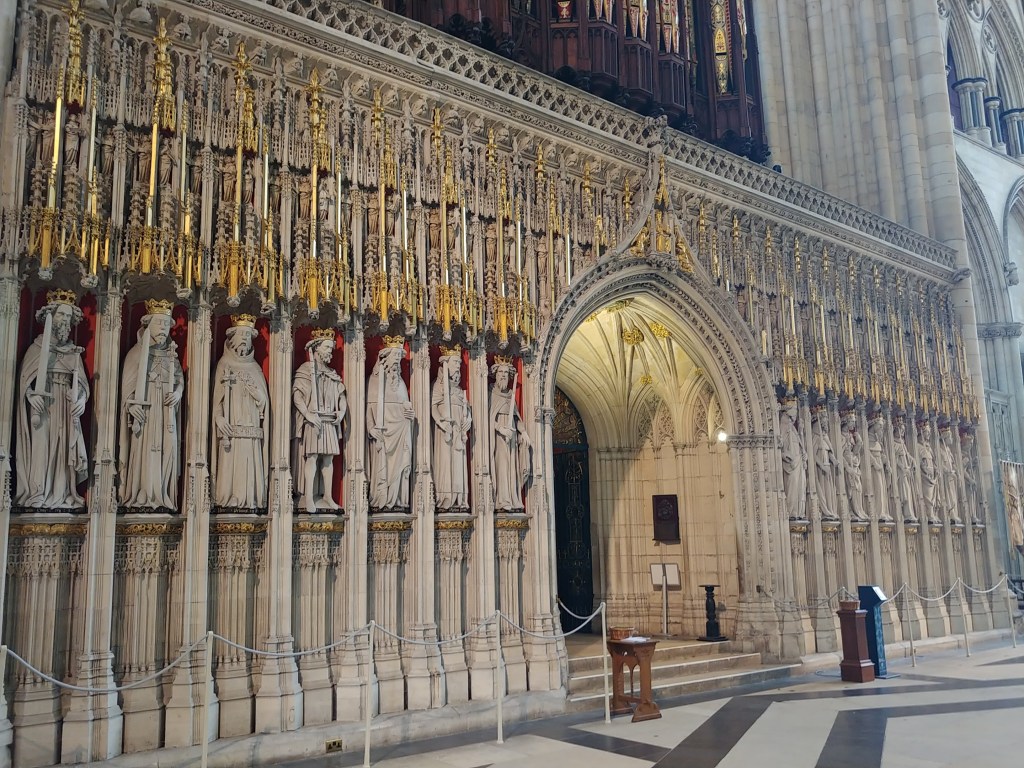

Another famous feature of York Minster is the Kings’ Screen, which separates the nave, where ordinary people worshipped in the medieval period, from the quire, where the choir and priest would have been. As its name suggests, the fifteenth-century Kings’ Screen depicts all English kings from William the Conqueror to Henry VI.

After World War II, two war memorials were added to York Minster. The King’s Book of York Heroes, a memorial to the fallen of the area, was presented to the cathedral in 1920; it features names, photographs, and biographies of men and women from York and the surrounding area who died in World War I. In 1925, another memorial in the Minster was dedicated: the Women of the Empire memorial screen. This memorial honors the women of the British Empire who died in the war.

These examples only scratch the surface of the many things to discover within York Minster. If you’re visiting York, make sure to leave an hour (or two or three) to explore the Minster and discover its history and architecture.

Leave a comment