With the coronation of King Charles III coming up in just over two weeks, I thought it was only fitting to look back at some notable coronations throughout the history of the British monarchy. So, without further ado, here are eight memorable coronations in history.

Coronation #1: William the Conqueror. After his victory over Harold Godwinson and the Anglo-Saxon army at the Battle of Hastings in October 1066, William and his Norman army marched on London, in order to capture the seat of political power in England and thereby force the surviving Anglo-Saxon elite to recognize his authority. In early December, William and his army crossed the Thames and soon after entered London. On Christmas Day (December 25) 1066, William had himself crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey. The service was conducted in both English and French, reflecting the linguistic divide between the English-speaking Anglo-Saxons and the French-speaking Normans. As William was proclaimed king at the climax of the ceremony, Normans and Saxons assembled inside shouted their approval. Norman soldiers stationed outside thought the noise was an assassination attempt and, in response, set fire to houses around Westminster Abbey. As smoke filled the Abbey, the congregation fled and riots broke out; somehow William and the clergymen officiating the coronation ritual finished the ceremony despite the chaos. While the riot marred the occasion, William’s coronation was a statement of Norman power intended to send a message to the Anglo-Saxon nobles who remained opposed to him. His coronation also set a precedent for all future English (and British) monarchs, all of whom, except two, have been crowned at Westminster Abbey. The two exceptions are Edward V, who was presumably murdered in the Tower of London before he could be crowned, and Edward VIII, who abdicated before his coronation.

Coronation #2: Richard I. Richard was crowned king in Westminster Abbey on September 3, 1189, having succeeded his father, Henry II, the first Plantagenet monarch of England. The solemn occasion of Richard’s coronation was marred by an outbreak of anti-Jewish violence. Jews (as well as women of all faiths) had been barred from the coronation, but English Jews came to London nonetheless to present gifts to the new king. Rumors circulated among the Christian population that Richard had ordered the Jews to be killed, and a mob attacked the Jewish residents of London. Many Jewish homes were destroyed; some Jews sought protection in the Tower of London, while others were killed. In the aftermath of the coronation violence, Richard ordered that Jews be left alone. However, he left on crusade soon afterward, and a new wave of anti-Jewish violence erupted in the spring of 1190, not just in London, but in York, Lincoln, and other cities.

Coronation #3: Elizabeth I. Elizabeth was crowned queen on January 15, 1559, after succeeding her older half-sister Mary I in November 1558. As was customary at the time, Elizabeth spent the night before her coronation in the Tower of London. For her, this occasion was doubly triumphant, as, just five years earlier, she had been in the Tower under very different circumstances. In the spring of 1554, Elizabeth was imprisoned in the Tower by Mary I for allegedly supporting Wyatt’s rebellion. Elizabeth’s return to the Tower as queen was thus a public declaration that she had survived and that she now had the opportunity and power to shape England as she wanted.

Coronation #4: Mary II and William III. William and Mary were crowned on April 11, 1689, having taken the throne after the deposition of Mary’s father, the Catholic James II, in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. To this date, their coronation is the only joint coronation – a coronation of two reigning monarchs, rather than a king and a queen consort – in British history. William and Mary’s status as joint monarchs reflected the fact that each of them had a claim to the throne: Mary as James II’s eldest surviving child, and William (Mary’s first cousin) as a grandson of Charles I. After James II was deposed in 1688, following the birth of a Catholic son (the presumed next monarch), Parliament invited the staunchly Protestant William and Mary, then rulers of the Dutch Republic, to invade England and claim the throne. Their coronation in 1689 was followed later that year by the Bill of Rights, which is often seen as the first step toward establishing a constitutional monarchy in Britain, as it limited the powers of the monarch. It also required the king – or queen – of England to be Protestant, preventing Catholics from taking the throne.

Coronation #5: George IV. George IV was crowned king on July 19, 1821, after succeeding his father George III in 1820. Reflecting his famously lavish taste, George’s coronation was the most extravagant ever staged; all participants were required to dress in Tudor and Stuart costumes, and George’s own coronation outfit cost more than £24,000 at the time. The coronation was also notable for the exclusion of the queen consort, George’s wife Caroline of Brunswick. The two had long been estranged, and, the year before, George had unsuccessfully attempted to divorce Caroline. As a result, he barred her from the coronation ceremony. Caroline, undeterred, still attempted to attend, but was turned away at the doors to Westminster Abbey. When Caroline tried to enter through a side door, it was slammed in her face. That same night, Caroline fell ill; three weeks later, she died, giving rise to rumors that she had been poisoned (however, she may have had cancer).

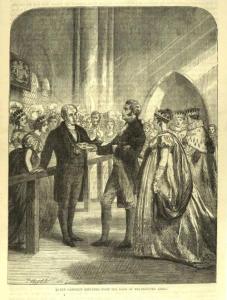

Coronation #6: Victoria. Victoria was crowned queen on June 28, 1838, after succeeding her uncle William IV in 1837. Her coronation was the first truly public coronation, as around 400,000 people came to London to watch the royal procession, aided in their journey by the development of railways in Britain. Victoria’s coronation was also the first time that the monarch traveled by coach to and from Westminster Abbey, which has been repeated in all subsequent coronations. A new crown was also made for Victoria, as it was believed that St. Edward’s Crown, which was traditionally used to crown the monarch at the climax of the coronation ritual, would be too heavy for her. The Imperial State Crown was crafted for the occasion; it is now used at State Openings of Parliament.

Coronation #7: Edward VII. Edward was crowned on August 9, 1902, after succeeding his mother Queen Victoria in 1901. His coronation was originally scheduled for June 26, but had to be postponed when, just a few days before the ceremony, Edward became seriously ill with an abdominal abscess and had to have emergency surgery. When the postponed coronation did occur, it was intended to be a celebration of the British Empire’s power. The ceremony was attended by the prime ministers of the Dominions (the white settler colonies) and 31 rulers of Indian princely states, which were nominally self-governing entities within the British Raj, but in reality were under British control. A number of colonial and Indian soldiers also participated in the coronation procession.

Coronation #8: Elizabeth II. Elizabeth was crowned on June 2, 1953, after succeeding her father George VI in 1952. Her coronation was the first in British history to be fully televised. While the procession at her parents’ coronation in 1937 had been filmed, cameras had not been allowed inside Westminster Abbey during the ceremony. Around 27 million people watched the live broadcast of Elizabeth’s coronation on the BBC. Film recordings of the ceremony were also flown to Canada and Australia so that they could be broadcast there.

Having attended his mother’s coronation at the age of four, King Charles is now preparing for his own coronation in a very different Britain. In a recognition of the diversity of the British people, Charles’s coronation will be the first to represent multiple faiths, cultures, and communities within Britain. It will also be the first coronation attended by a British prime minister of color. Furthermore, this will be the first coronation to be livestreamed online, as well as broadcast live on television. More seriously, Charles’s coronation will likely – if it has not already – stimulate conversations about the future of the monarchy in Britain, especially since, as the coronation is a state occasion, it is paid for by the British government. As the British monarch is the only remaining European monarch to be formally crowned in a coronation ceremony, the question must be asked: is a coronation still a necessary ceremony in the twenty-first century world? Only time will tell.

Leave a comment