After completing yet another rewatch of Derry Girls – which, by the way, is one of my favorite shows – last night, I found myself reflecting on an exhibition I visited at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) during my trip to London in December. Technically speaking, there are a number of exhibitions at the Imperial War Museum that exhibit difficult history, as the museum focuses on 20th century conflicts and related events, including the First and Second World Wars and the Holocaust. For this post, I’m going to confine my reflections to Northern Ireland: Living with the Troubles, a temporary exhibition on display at IWM London in 2023.

Before I share my thoughts on this exhibition, a little bit of background information is required. First, if you are not familiar with Derry Girls, it is a sitcom focused on four teenage girls and one boy living in Derry/Londonderry (Catholics and Protestants use different names for the city) in the mid-1990s. While Derry Girls is primarily a comedy – and a very funny one, at that – it doesn’t shy away from its setting. Interwoven with the story of the Derry Girls are the realities of life in Northern Ireland in the mid-1990s, the final decade of the Troubles. For three seasons, the Derry Girls grow up in the shadow of the Troubles, until the show ends with the referendum on the Good Friday Agreement, the peace treaty that brought an end to the Troubles after thirty years of conflict. The Derry Girls thus enter adulthood just as Northern Ireland gets a chance at a different future. Derry Girls is an excellent show, and I highly recommend it.

So what were the Troubles? The history of the Troubles is far too complex to be explained in one blog post, but, in short, the Troubles were a thirty-year period of sectarian conflict and violence in Northern Ireland, lasting from the late 1960s until 1998. At the heart of the Troubles was the conflict between unionists/loyalists on the one side, who were mainly Protestant and wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom, and on the other side, Irish nationalists and republicans, who were mainly Catholic and wanted Northern Ireland to be part of a united Ireland. Key players in the conflict included the British army, which intervened in Northern Ireland beginning in 1969; the Royal Ulster Constabulary, the overwhelmingly-Protestant police force; unionist paramilitaries; and republican paramilitaries, most famously the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

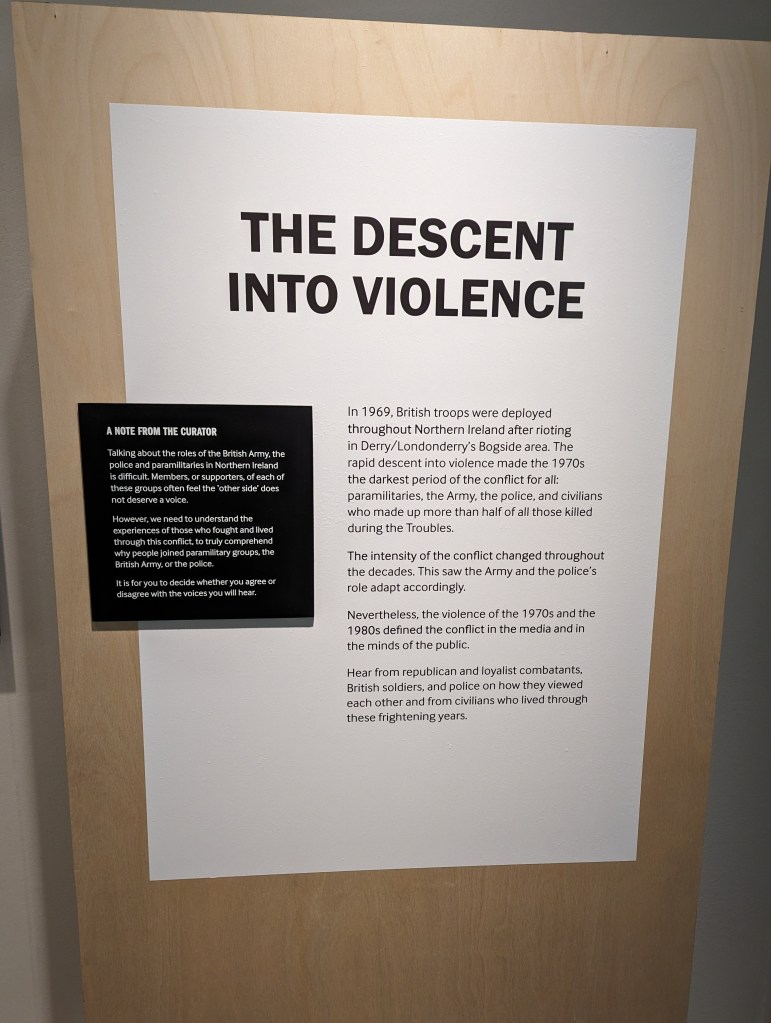

The Troubles began in the late 1960s, when Catholics in Northern Ireland began a civil rights campaign aimed at ending discrimination against the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland. The government in Northern Ireland responded by attempting to crush the protests, leading to riots throughout Northern Ireland in August 1969 and the deployment of British troops to Northern Ireland in order to support the unionist government of Northern Ireland. The Troubles was very much a multi-way conflict, as republican paramilitaries carried out a guerilla campaign against British forces in Northern Ireland, as well as a bombing campaign in both Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. Republican paramilitaries and loyalist paramilitaries fought each other, while the British army carried out policing and launched a counterinsurgency campaign. At times, the British forces perpetrated violence themselves, as in the case of Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march in Derry/Londonderry. The Troubles led not only to violence in Northern Ireland, but also to the increasing segregation of the Protestant and Catholic communities, symbolized by the construction of so-called “peace walls” to keep the two communities apart.

One final historical note: I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that the history of conflict in Northern Ireland is much longer than the history of the Troubles. You could easily date the beginning of the Northern Ireland conflict to the division of Ireland in 1921 in the wake of the Irish War of Independence, or even to the settlement/colonization of northern Ireland by Protestant English and Scottish settlers in the 17th century, which created a Protestant-minority ruling class in what would become Northern Ireland.

How do museums interpret a difficult history like the Troubles? By “difficult history,” I mean a period of history that is painful to learn about because it was characterized by violence, oppression, and/or suffering. In many (but not all) cases, difficult histories can be contentious, as people don’t agree on how these histories should be interpreted. Examples of difficult histories that are both painful and contested include the history of slavery and racism in the United States and the history of the British Empire in the UK. The history of Nazism and the Holocaust is a difficult history, in that it is painful to learn about, but its interpretation is not contested in the same way as the other histories I mentioned.

While people outside of the UK may be less familiar with the history of the Troubles, the period is still a very sensitive subject within the UK. Although the Troubles are over, the Northern Ireland conflict has yet to be fully resolved, as political conflict and sectarian tensions remain, many of which were stirred up by Brexit and the resulting issue of a potential hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Because the Troubles are such a sensitive issue still in the UK, I was very interested to see how the Imperial War Museum would present this history in its temporary exhibition Northern Ireland: Living with the Troubles. The exhibition focused on people’s experiences during the Troubles and the sharply differing perspectives that people in Northern Ireland had (and still have) on events that happened during the Troubles.

I don’t know enough about the history of the Troubles to judge the Imperial War Museum’s exhibition from a historical perspective. However, looking at the exhibition from the perspective of a public historian, I found its construction to be unique. I don’t mean the actual, physical construction of the exhibition, but rather the tone and content of the exhibition’s text panels. In the majority of exhibitions at history museums, the curator’s voice is heard only through the choice of content for the exhibition’s panels and artifacts to be displayed in the exhibition. Curators usually do not directly insert their voices into an exhibition, instead remaining largely invisible behind the texts and artifacts that make up the exhibition.

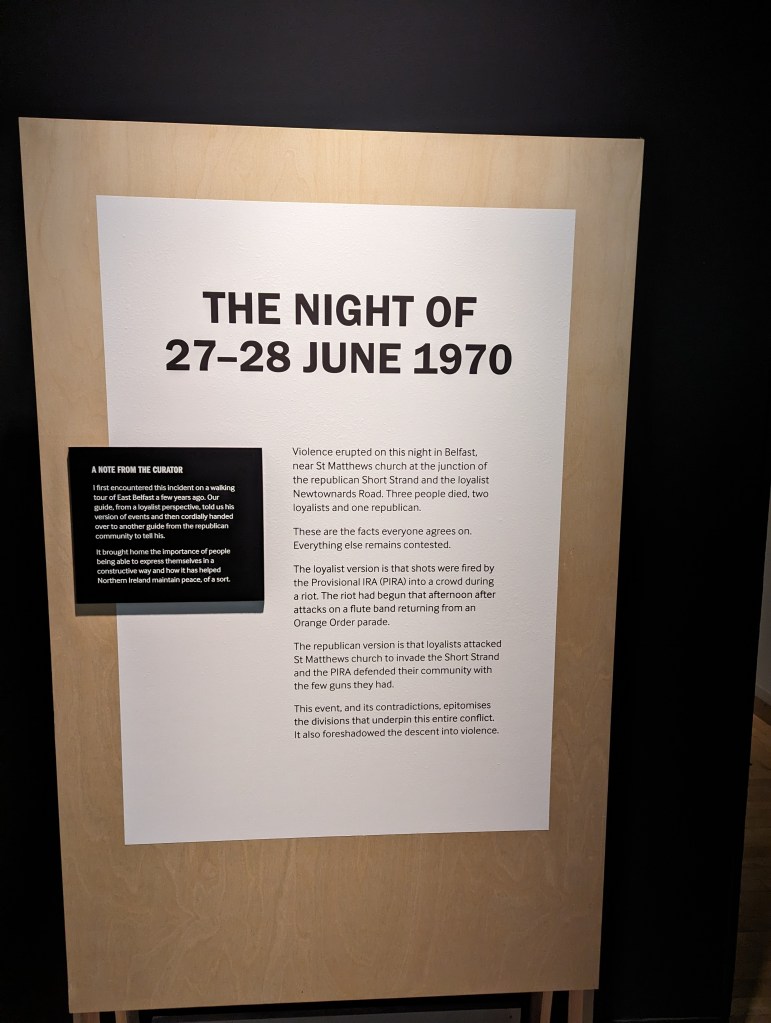

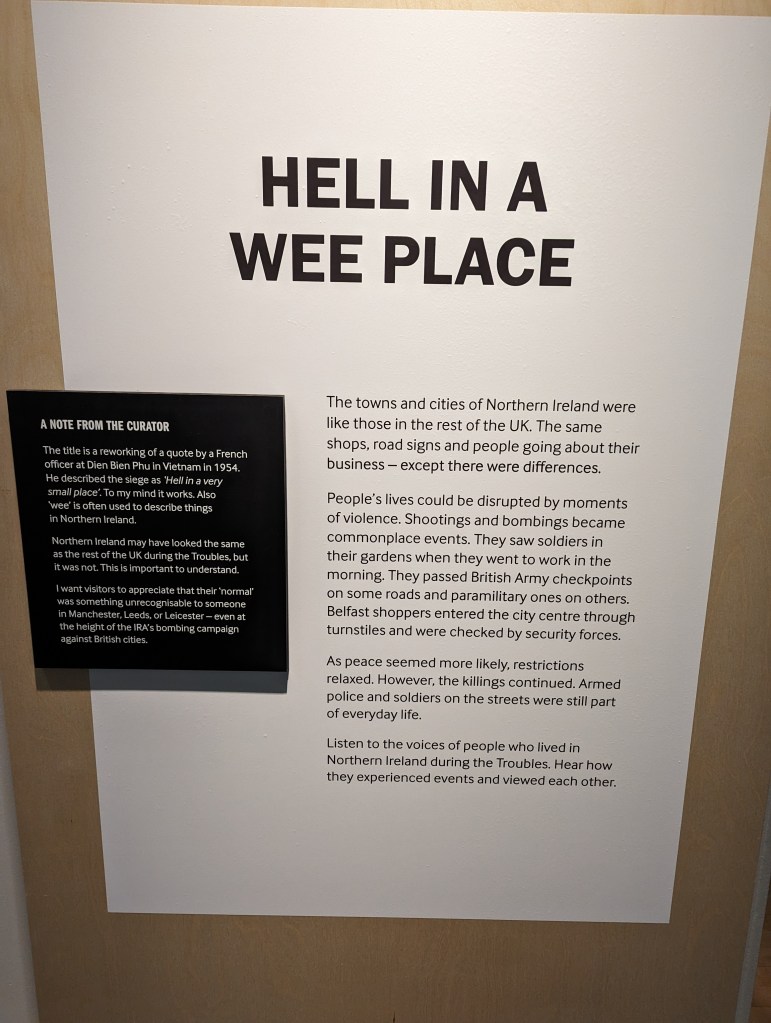

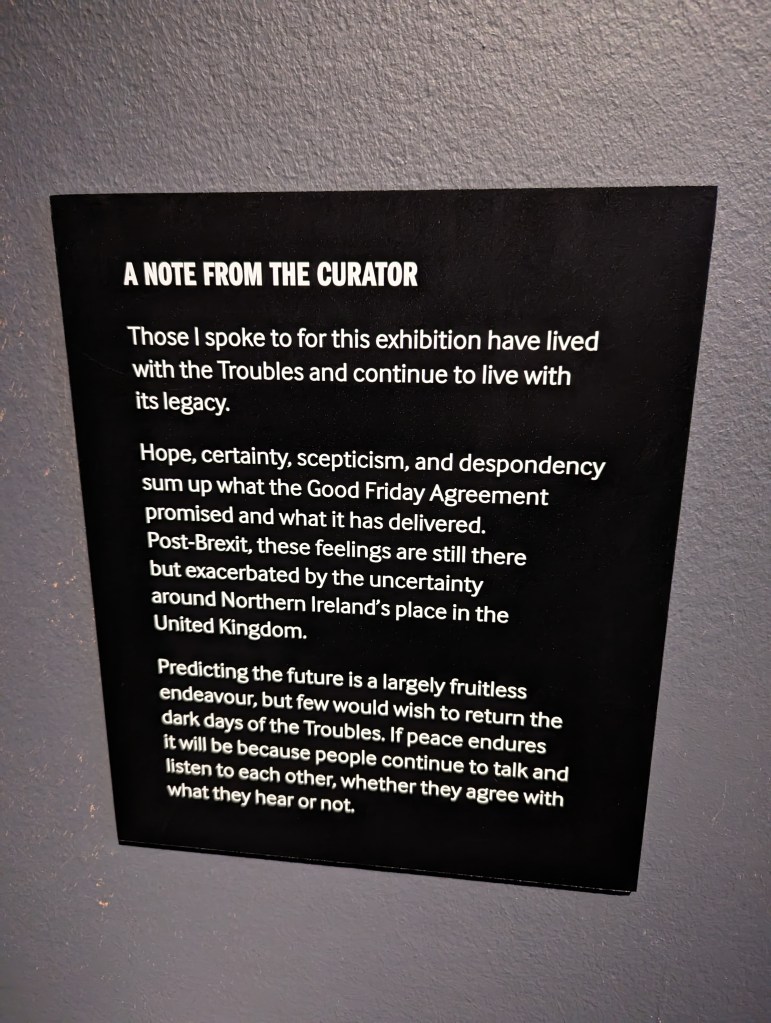

In the case of IWM London’s Northern Ireland exhibition, the curator did not remain invisible, but rather inserted their voice directly into the exhibition. The main text panel in each section of the exhibition included a box entitled “A Note from the Curator.” The content of these notes varied depending on the content of the panel they appeared on, but they included personal reflections from the curator, reminders to visitors that there is no one “correct” perspective on the Troubles, and a call for continued dialogue between unionists and republicans in Northern Ireland. Additionally, one curator’s note emphasized the fact that what was considered “normal” in Northern Ireland during the Troubles was very different from what was considered “normal” in the rest of the UK, because of the constant threat of violence and physical reminders of the conflict, such as patrolling British soldiers and checkpoints at the entrances of neighborhoods or shopping centers.

As I see it, the purpose of the curator’s notes in the Northern Ireland exhibition was two-fold. First, some of the notes explained specific decisions made relating to the exhibition, such as the decision to title one of the panels “Hell in a Wee Place,” a reference to the Vietnam War that encourages visitors to see the Troubles as a war, though one of a different kind. Secondly, the curator’s notes encourage visitors, especially visitors from the UK who remember the Troubles, to interrogate their knee-jerk reactions to the content presented in the exhibition. One panel in particular urged visitors not to dismiss the other side’s perspective out of hand, even if they disagree with it.

All in all, I found Northern Ireland: Living with the Troubles to be a very interesting exhibition and the curator’s choice to abandon their traditional invisibility to be an appropriate one given the topic of the exhibition. I think that this approach to curation – that is, notes from the curator being incorporated into the text of an exhibition – could be appropriate and productive in exhibitions on the history of slavery, the Civil War, and, especially, the memory of the Civil War in the United States. IWM London’s Northern Ireland exhibition stands as an excellent example of how museums can interpret a difficult history that is both painful and contentious. This year, the exhibition is moving from IWM London to IWM North in Manchester (where it will be from late March to late September). If you will be in the UK this year and are interested in the history of the Troubles or how museums interpret difficult histories, I encourage you to visit this thought-provoking exhibition (and maybe watch Derry Girls, while you’re at it).

Leave a comment