Note: This is the second in a series of posts on the history of York, England. You can find the previous posts here.

The band of people – warriors, artisans, women, and children – arrived at the place where two rivers came together after a long journey across the sea. Looking around, they decided it was an excellent place to settle. The two rivers provided water, fish, and natural defenses against invaders, as well as a navigable route to the North Sea. The newcomers set about constructing wooden homes, creating a town they called Eoforwic.

The scene just described is exactly that: a scene, a historian’s imagining of what might have happened when the first Anglo-Saxons arrived at the place we call York. Is this really what occurred? We don’t know. There are very few sources of information about the Anglo-Saxon period in York, so we have more mysteries than concrete answers. Imagination is sometimes required to fill in the gaps. But who were the Anglo-Saxons, and how did they come to settle at York? To answer that, we first have to go back to the late Roman period.

York (known as Eboracum to the Romans) had thrived as a frontier settlement since its founding in 71 CE. Everything changed, however, as the Western Roman Empire became increasingly unstable in the early 5th century CE. Facing repeated invasions by Goths and other Germanic peoples, Rome withdrew its forces from Britain – its most far-flung province – in 410 CE in order to focus on defending the empire’s heartland. The people of Britannia were on their own.

What happened after the Romans withdrew from Eboracum? We simply don’t know. After the Roman withdrawal, Eboracum disappears from the historical record for about two hundred years. The area may have been abandoned entirely after the Romans left, or some people may have continued to live there, though in a smaller settlement than before. Only in the 7th century does York reappear in the historical record, now occupied by a new group of people.

Chapter 2: Eorforwic

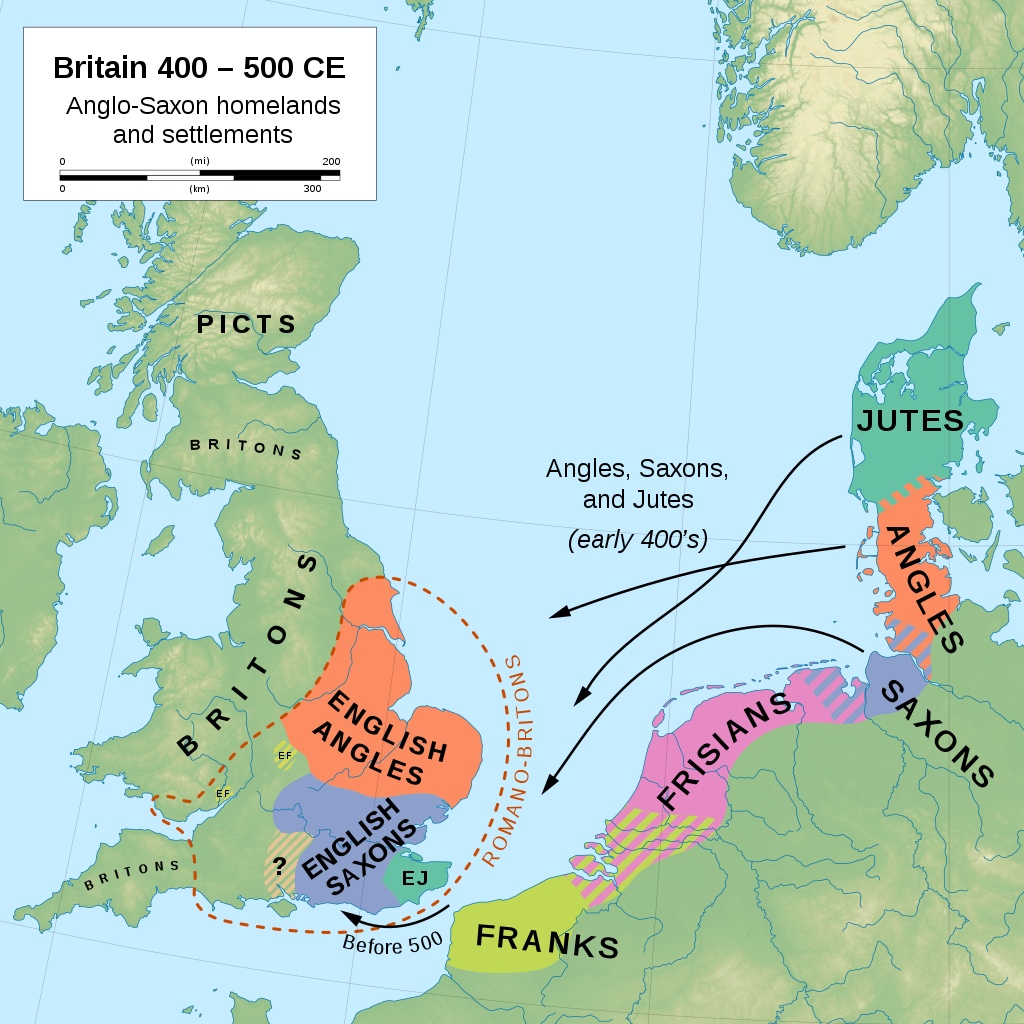

During the missing two centuries of York’s history, Britain had changed significantly. The Roman withdrawal from Britain in 410 CE had created a power vacuum, one which other peoples were only too willing to fill. In the early to mid-5th century CE, three Germanic peoples – the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes – migrated from continental Europe to Britain. These peoples sought new lands for settlement, as well as an escape from the turmoil of post-Roman western Europe. Britain, abandoned by the Romans and lacking a ruling class, appeared to be the perfect place to settle.

Known today as the Anglo-Saxons, the Germanic migrants settled in Britain over the course of several centuries, from the 5th century until the 7th century CE. During this period, the Anglo-Saxons filled the power vacuum created by the Roman withdrawal, becoming the dominant political power in what is now England. One of the first mysteries of the Anglo-Saxon period is how, precisely, the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain occurred. There are very few written sources dating to this period, so what we do know about the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain comes from archaeological evidence.

One theory of Anglo-Saxon settlement is that a large group of Anglo-Saxons migrated to and violently conquered Britain, killing a significant number of the existing inhabitants. The Anglo-Saxons then repopulated Britain with further Anglo-Saxon migrants. However, a more modern theory, based on archaeological evidence, material culture, and DNA analysis, posits that a small group of elite Anglo-Saxon warriors migrated to Britain and gained political and social dominance without the wholesale killing of the existing inhabitants. The Anglo-Saxon incomers, the theory continues, then intermarried with the existing Romano-British population, beginning a process of acculturation of the Romano-British people to the Anglo-Saxon language and culture. For instance, archaeologists have found that although material culture – the objects of daily life – changed significantly after the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, patterns of land use and settlement remained much the same in Britain, suggesting that the Romano-British population continued to live on and tend their land. Today, the acculturation theory is the most widely accepted view of Anglo-Saxon settlement among scholars of this period.

Between the 5th and 10th centuries, the Anglo-Saxons ruled seven kingdoms in Britain: East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, Wessex, Essex, Kent, and Sussex. York, whether inhabited or not, was part of the kingdom of Northumbria, the northernmost of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. This period of Anglo-Saxon rule is often called the Heptarchy, after the seven kingdoms. During the Heptarchy, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were distinct political entities, ruled independently of each other.

It is in the early 7th century, during the Heptarchy, that York reappears in the written historical record. Whether the area had remained inhabited or not is still unknown, but in the early 600s, King Edwin of Northumbria decided to make the old Roman town of Eboracum – now renamed Eoforwic – his chief city. In 627, Edwin converted to Christianity and built the first wooden minster (or cathedral) in Eorforwic. No trace of this first minster in York has survived.

It is not only the Anglo-Saxon minster in York that didn’t survive. Only one structure from the Anglo-Saxon period is still extant today in York. The Anglo-Saxons generally constructed their buildings from wood, which doesn’t survive long-term in the same way that stone or brick does. In fact, the Anglo-Saxon structure that does survive in York is a stone tower built into the city walls.

In addition to a lack of architectural evidence for the Anglo-Saxon period in York, there is also a lack of documentary evidence. The Anglo-Saxons didn’t leave behind the same volume of written records as the Romans did; this is especially true for the early period of Anglo-Saxon rule. Consequently, historians don’t know as much about Eoforwic as they do about Roman Eboracum. What we do know about Anglo-Saxon York comes primarily from archaeological evidence, through finds such as the Coppergate Helmet, an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon helmet discovered in York in 1982.

In the centuries following its elevation to capital city by King Edwin, Eoforwic continued its second life as an Anglo-Saxon city. During this time, the Heptarchy was unified, becoming the kingdom of England. Although Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, had called himself “King of the Anglo-Saxons” in the late 9th century, he did not rule the entirety of what later became England, as the Vikings occupied and ruled the northeastern Anglo-Saxon lands at this time. It was not until the rule of King Athelstan in the early 10th century that England was united as a kingdom. In 927, Athelstan conquered the last remaining Viking kingdom, restoring Anglo-Saxon rule in all of the Anglo-Saxon lands. However, the Viking threat was not vanquished for long. The newly-united kingdom of England remained a major target of Viking raids and invasions. Why did the Vikings raid England? Why did they occupy and settle in northeastern England, including in York? And how did the Vikings change the culture of the areas they settled? Chapter 3 will take up these questions, as I explore the history of Viking York.

Leave a comment