Every spring, daffodils planted around Clifford’s Tower, the only remaining part of York Castle, bloom, covering the mound on which the tower sits in a carpet of yellow. A curious passerby might ask why the daffodils were planted in the first place. Was it part of a city beautification project? Do the daffodils symbolize something related to the history of York Castle? The answer is closer to the latter than the former. In the 20th century, the daffodils were planted around Clifford’s Tower as a memorial to a dark episode in the castle’s history: a pogrom in 1190.

Pogroms, or a violent, often deadly, attacks against Jews, are perhaps more commonly associated with the 19th and 20th centuries. There were several waves of pogroms in late 19th- and early 20th-century Russia, for example. In 1938, the Nazis perpetrated a major pogrom against German and Austrian Jews called Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, Sadly, there are many other examples of pogroms in the 19th and 20th centuries – and in earlier centuries as well. The medieval and early modern periods were not devoid of organized violence against Jews. For example, during the First Crusade, several thousand Jews living in cities along the Rhine in what is now Germany (such as Mainz, Worms, and Speyer) were murdered by crusaders making their way toward Constantinople.

Nor was medieval antisemitism confined to continental Europe. In the late 12th century, England had a growing Jewish community, the first Jews having come to England after the Norman Conquest of 1066. At the time, religious laws prevented Christians from working as moneylenders, a role filled by Jews. Jewish moneylenders provided an essential service for the medieval economy, but they were subject to great religious prejudice and economic-related hostility from their Christian neighbors. Beginning in the mid-12th century, religious prejudice against Jews started to take the form of accusations of ritual murder. Indeed, the first known accusation of the blood libel – the antisemitic myth that Jews use the blood of Christian children in religious rituals – occurred in England in 1144, when the Jews of Norwich were falsely accused of ritual murder after a young boy, William of Norwich, was found dead. Similar claims of ritual murder occurred in Gloucester in 1168, Bury St. Edmunds in 1181, and Bristol in 1183.

In 1189, violence against Jews broke out in London, when Jews attending the coronation of King Richard I were attacked. One secondhand account states that two Jewish citizens of York traveled to London for the coronation; one of the men was attacked and killed on the way home. The causes of this upsurge of violence against Jews were both religious and economic. New taxies had been levied in England in order to fund the Third Crusade, which angered Londoners; additionally, as the case of the First Crusade indicates, the increase of religious fervor surrounding a crusade often resulted in violence against non-Christian groups.

It was in this climate of antisemitism and violence against Jews that the pogrom in York occurred in March 1190. When an accidental house fire broke out in York, a Christian mob, led by Richard Richard Malebisse, exploited the chaos to break into the house of a Jewish resident of York. The mob looted the property and killed everyone inside. Understanding the threat to the Jews of York, Joceus, the leader of the Jewish community, led all of the Jews to York Castle in order to seek protection from royal officials.

Joceus and the Jews of York reached the castle and took refuge in the castle’s tower, which was almost certainly on the site of the present Clifford’s Tower. However, relations between the Jews and the keeper of the tower were tense, and when the official left the tower on other business, the Jews refused to allow him back in, fearing that he might lead the mob in or turn them over to the sheriff. A siege thus developed, with the sheriff’s men outside, surrounding the tower, and the Jews inside the tower.

According to several accounts, on March 16, which was the sabbath before the beginning of Passover, the Jews of York realized that they could not hold out much longer against the mob. Rather than waiting to be killed by the mob or being forcibly baptized as Christians, the leaders of the Jewish community decided on an act of collective suicide. Each man would kill his wife and children, before taking his own life. Before their deaths, the Jews also set fire to their possessions; the fire soon spread to the wooden tower, destroying it. No one knows exactly how many Jews died in the castle. Estimates range from 20 to 40 families, and one account stated that around 150 Jews died.

Richard Malebisse, one of the leaders of the mob, had offered safe passage to any Jews who agreed to convert to Christianity. However, the few Jews who took up his offer soon discovered that it was not genuine; they were killed by the mob as soon as they left the tower. After the massacre, the leaders of the mob destroyed the records of Christian residents’ debts to Jews, seeking to remove evidence of a motivation for the pogrom (and cover up who had been involved). In the aftermath of the events of March 1190, fines of up to £66 were imposed on 59 leading families in York, many of whom had either been involved in the massacre or knew who had been. The castle’s tower, which had been destroyed during the massacre, was rebuilt in wood, then replaced in the mid-13th century with a stone tower: Clifford’s Tower, the ruins of which still stand today.

What happened to York’s Jewish community after the pogrom of 1190? A new Jewish community was soon established in York. However, in 1290, Edward I ordered the expulsion of all Jews from England, destroying York’s Jewish community once again. Jews were only permitted to return to England in 1655, when Oliver Cromwell allowed a small community of Sephardic Jews to settle in London, after which the Jewish population in England began to grow once again. It was not until the mid-19th century, though, that Jews received full legal and political rights in England.

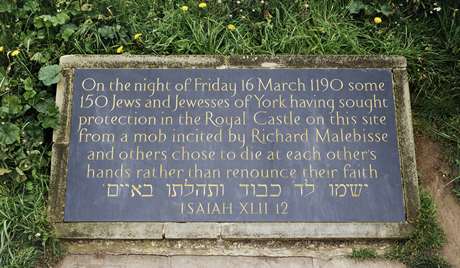

By the early 20th century (if not before), Clifford’s Tower had become a heritage site in York. For many years, however, the pogrom of 1190 remained a hidden history, not mentioned in histories of and guidebooks to the castle. It was not until 1978 that a memorial plaque commemorating the massacre was installed at the base of the tower. The daffodils were planted on the tower’s mound in 1992 as a yearly memorial to the massacre. Why daffodils, you might ask? Their six-pointed shape was thought to evoke the Star of David.

While it is important that the massacre of York’s Jews is now commemorated at Clifford’s Tower, the existing physical memorialization is relatively unobtrusive. A visitor could easily miss the plaque commemorating the pogrom on their way to climb the steps of Clifford’s Tower and take in the view of York. Similarly, how many visitors – or residents of York, for that matter – understand the meaning of the daffodils, which only bloom for a short part of each year? English Heritage, which manages Clifford’s Tower, has made an effort to place the pogrom of 1190 back in the history of York Castle. The English Heritage website for Clifford’s Tower provides a history of the massacre, and discusses the events of 1190 in the larger context of the castle’s history. An English Heritage-produced podcast also delves into the history of the massacre and its meaning for York’s Jewish community today. Visitors interested in learning more about the history of York Castle and medieval Judaism are likely to seek out such resources; others will not, which is why physical memorialization and interpretation is so important. It would be interesting to know whether English Heritage has incorporated the story of the pogrom of 1190 into the interpretation at Clifford’s Tower, which recently reopened after a £5 million conservation project, which transformed the visitor experience at the site. I may just have to visit and find out for myself when I’m next in York.

Leave a reply to Coronations in History – Making the Past Present Cancel reply